Monthly Archives: March 2008

I have talked a lot about the prospect of Uru players creating worlds after Cyan shuts the game down. But I haven't said much about the fan Myst projects that exist today.

Quite a number have been started over the years; Cyan is generally willing to give permission if you ask nicely. Some exist as small web-based adventures, such as the now-vanished D'ni Legacy. Some are planned as full-scale downloadable games, such as The Ages of Ilathid -- ambitious, but making slow and uncertain progress.

A year ago, in April of 2007, I ran a small game directly on the Uru web forums. Plum Lake was pure text -- because that's what I'm good at, that's why. (Okay, I included one illustration.) I took the standard text-adventure model and ran it interactively. I would post to the forum, describing where I was and what I saw. Then I'd open the floor to suggestions on what I should do next.

My game ran for about two weeks, and concluded satisfactorily. The players reached the end of what I'd designed, and I decided it was an experiment well run.

A few months later, a player called Norfren began running something that comprehensively and conclusively blew my game's pants off.

He began by posting several images notionally captured in the Age of Minkata. Cyan had opened Minkata in May; it was an expansive but barren world, hemmed in by blinding dust-storms. Norfren's images were not actually from Uru, but people were willing to accept them as an extension because they were imaginative and nicely rendered. (Using POVRay, a free ray-tracing package. Some of the images have Uru avatars edited in.)

Over the next couple of weeks, Norfren began describing his journey across Minkata in a first-person, narrative style... and in plural: "we are here, we are doing these things." And the readers played along, describing what they were doing as members of the exploratory party.

By the end of October, the scenario included puzzles and linking books, and the readers were fully engaged -- solving the puzzles and allowing the narrative to advance. They found their way underground, explored a series of aqueducts and tunnels, found a link to an undiscovered section of the D'ni city, and so on.

(Warning: Posts in the forum thread consistently use Javascript spoiler tags to hide both large images and puzzle solutions. However, due to a recent server change, the spoiler tags are currently nonfunctional -- everything is visible up front.)

Throughout this process, the bottleneck remained Norfren's ability to render new art. He could respond to ad-hoc ideas to some extent, but had to provide fairly clear hints about what to do, and occasionally nudge players back into the areas that he was preparing. The players were quite willing to go along with this.

In late December, Norfren posted images on his own web site, in order to accomodate some animated details. In late January he included a 360-degree view, and then a puzzle that responded interactively. And in early February, as we were digesting the news of Uru's cancellation, a complete (if tiny) Age to look around. (Contributed by vikike176, in collaboration with Norfren.)

By the way, I'm focussing on the designer's work here, but don't get the idea that the thread is all his. Most of the text is the player group, poking around, making suggestions, goofing off, adding their own wrinkles to the narrative. Everyone is clearly deferring to Norfren as the "game master" -- nobody is posting their own images of unexplored areas, for example. But the tone of the thread is the players telling their story, not Norfren telling a story to them.

Finally, in March, a puzzle unlocked a fully explorable Age, complete with clues, puzzles, links to other Ages, a maze, and finally a link home to Relto, which resolved the story. I don't know if the author intends to continue, but it's enough of a stopping point for me to blog about it: six months and over 900 posts, including dozens of images.

So what does this tell us?

"Surprise in Minkata" (I have no other title for it) constitutes the biggest chunk of exploration in the Myst universe since Cyan ended its Age releases. The visual quality is not on the level of a modern commercial adventure game; but it's easily comparable with the original Myst, or with other one-man adventure creations like Rhem. I could quibble with the placement of navigation hotspots in the final Age. But, overall, it's effectively a player-contributed Uru episode.

I think that if the game had continued, we would have seen more like this. And with no Uru in operation? The audience is clearly waning, but the most dedicated players remain. We will see what the coming year yields.

Tags: fanfic, forum games, myst.

Despite my earlier attempts to fine-tune things, almost every perfectly legitimate comment posted here within the last week has been marked as spam by our blog software. Since the only "spam" we were getting was made of misfiled real comments, I'm guessing that our CAPTCHA is doing its job just fine, and I've made further adjustments reflecting this to the spam filter.

Sorry, again - all your comments are up now. We'll keep a closer eye on things and make sure this doesn't happen a third time (fooey).

Tags: administrivia.

Hey, remember Tetris? Check out these Tetris gameshelves! Except you'd have to stack them with holes on each level or else your games will disappear. Which reminds me of a recent favorite explodingdog drawing.

Tags: classic games, computer games, explodingdog, furniture, gameshelves, tetris.

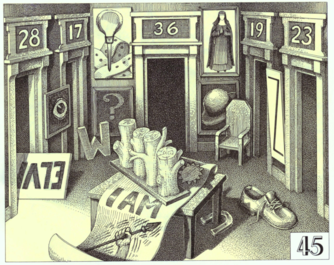

At a local gathering of friends the other day, the classic puzzle book Maze, by Christopher Manson, came up in conversation. Many, myself included, recalled encountering it not too long after its original 1985 publication date. At the time, we all found it a fascinating artifact, though a completely inscrutable puzzle.

The book is still for sale, as it turns out, and there's also an online, hypertext version of the book you can wander through freely. (I note that the website appears to reside among the archives of an early electronic-publishing venture, and has remained unmodified since the mid-1990s. Sadly, the scanned illustrations are formatted to fit the relatively dinky computer displays of that era, resulting in much of the fine detail getting lost. I suppose I should encourage you to go buy the book, if you find them sufficiently intriguing.)

I should correct myself and call the book semi-scrutable, at least. It represents a labyrinth of connected chambers, you see, where each page features a haunting and evocative illustration of one room, trimmed with a short bit of text where the book's mysterious narrator leads a group of squabbling explorers through. The first part of the book's puzzle, then, is simply to find a path that takes you from the entrance to the maze's center and back in 16 steps. The harder part involves teasing the text of a riddle out of all the depicted stuff that lay along this route. And this is where most mortals get stopped, finding themselves with a pile of stuff and no clues.

I should correct myself and call the book semi-scrutable, at least. It represents a labyrinth of connected chambers, you see, where each page features a haunting and evocative illustration of one room, trimmed with a short bit of text where the book's mysterious narrator leads a group of squabbling explorers through. The first part of the book's puzzle, then, is simply to find a path that takes you from the entrance to the maze's center and back in 16 steps. The harder part involves teasing the text of a riddle out of all the depicted stuff that lay along this route. And this is where most mortals get stopped, finding themselves with a pile of stuff and no clues.

After I returned home that evening, it occurred to me that I probably hadn't thought much about Maze since the ascent of Wikipedia, and surely it spelled out the solution. Why, yes. And what a solution! It's amusing I can look at this more than 20 years after the book's original publication and tell you why this would get razzed by any of the hardcore puzzle people I know today.

Granted, it was supposed to be very hard, because there was a cash-money prize for the first correct response. But the Wikipedia article implies that they overdid it, since the publishers extended the deadline at least once, and it's unclear if any claim was ever made. And no wonder, really; the solution demands you selectively perform wordplay on picture and text elements along the path, but gives you no clues as to which elements are important, and what should be done with them.

For example (and I'm about to get a little spoilery here) on this page, it happens that you're supposed to get a word by taking two picture elements and anagramming them together. But for all you know, maybe you combine the A with BELL and perform a sound-alike wordplay to get ABLE. Or perhaps the word is simply BELL, after all. Or a dozen other things suggested by the image. They all seem equally right - which is to say, none especially so.

Carry this feeling over the path's 16 pages, and I assert you've got an utterly unsolvable combinatorial explosion. I would be quite interested to learn of integral clues I'm overlooking, though, or to hear about someone who solved the book without any hints! Until then, I must conclude that for all the book's beauty - and it is quite a lovely thing to flip through - as a puzzle, it would get booed off the stage at the MIT mystery hunt.

More important than its puzzle, however, is the book's legacy. Without a doubt, the book left a lasting inspiration to many, stoking a hunger to try solving more baroque and beautiful puzzles, even if that means having to create them first. You can see echoes of Maze in art-heavy digital adventures such as Myst. In fact, the stimulus for this group recollection among friends was a new puzzle designed with Maze in mind, by Gameshelf pal Andrew Plotkin. I have it on good authority that it was cracked by dedicated solvers within a day.

Tags: books, game history, history, maze, myst, puzzles, the mit mystery hunt.

Uru Live is scheduled to be shut down in a bit over two weeks, as I write this. Cyan has not made any public pronouncement about what they will do next. They haven't said if the online version of Uru will remain available in any form.

(We know that Gametap will return Uru: Ages Beyond Myst to their rental service. That's the original single-player Uru game -- without even the expansion packs -- and you can't hack Gametap downloads to add new content. The news is therefore irrelevant to me. I'm interested in Uru as a shared, extendable universe.)

My last post worked around to the idea of a fan-created Uru game. Not an extension of the existing Uru, not managed by Cyan; a completely new system, open-source and run by the players. This post contains my sketch of how to do it.

In other words, this post will be too technical for the game nerds, and too handywavy for the programmers. I have no code to back it up. I have experience running a multiplayer gaming service... which has never had more than a dozen people online at a time. So -- dismiss away, if you want.

On the up side, the technical issues here are not specific to Uru or to the Myst universe. Want to run a graphical MMO adventure? Here's a plan. Go to town with it.

So...

How would I design a fan-run Uru-inspired game?

This post is speculative -- in fact, completely hypothetical. If:

- Cyan shuts down the Uru servers on April 10th, and

- they do not offer any future plans for Uru, and

- a group of Uru players want to begin operating a new multiplayer adventure environment for the Uru community, and

- I were making all the decisions,

...then what would I build?

This post does not rise to the level of a proposal. It's a sketch; it's my answers to a bunch of hypothetical questions. I'll argue the merits of each point separately; you don't have to accept my ideas on one point just because you buy another.

This is a conservative proposal; it's a system I think I could build. However, I am not volunteering to build it. Planning is the fun part. I have too many unfinished projects already to pick up a new one. But I can gab about ideas all day. Lucky you, eh?

Assumptions

I want a multiplayer, graphical, 3D environment that approximates what people did in Uru Live.

I will rely entirely on open-source software. Cyan's Plasma engine will not be used.

I do not want to infringe on Cyan's ownership of the Myst series, or their ability to bring back Uru Live someday. (It will always be true that Cyan might bring back Uru Live.)

The plan will be implemented by a small group of part-time programmers. (Not crazy genius programmers; just programmers.) (Maybe I am a crazy genius programmer, but I'm not volunteering to build this, right?)

The result does not have to be as impressive as Uru Live. (See previous point!) We can tolerate shakier graphics, less scalability, and so on, because we have no budget and nobody's doing this full-time.

The game world consists of a set of small areas -- Ages, in Myst parlance. Each Age is replicated in many instances. Any player or group can get an instance of their own; instances are cheap to create on the fly.

The goal is for players to hang out in the environments and chat.

The goal (also!) is for players to contribute new Ages, and explore each others' Ages.

Socializing happens in medium-sized groups -- perhaps twenty or thirty. That's the size of a conversation. Getting a hundred people together in one place would be neat, but it's not a design goal.

Exploring is done alone, or in small groups. Interactive environments stop being fun when a bunch of strangers are jumping in front of you and messing with your stuff. Adventure-style game logic -- with specific, discrete actions and unique results -- tends to have a small number of actor roles. When you have a hundred people cooperating on a task, that's CRPG design, not adventure design.

In other words: while I want a game world that encompasses hundreds or thousands of people, I'm not worried about rendering them on the a single screen or managing their simultaneous access to a single real-time puzzle.

Overall Architecture

The plan in short:

- many independent shards

- but probably one shard is the "main" or common shard

- each shard can contain many Ages, at the shard owner's discretion

- anyone can run a shard, if you have a server with Python and MySQL

- Jabber is the communication layer

- an Age instance is a Jabber MUC (chat room)

- Ogre3D is the client 3D engine

- scripting is in Python (both client-side and server-side)

- limited character animation

- no physics

- storyline is not my problem

The Shards

A "shard" is a stand-alone, fully functional server running the game system. (It might actually be several machines, but imagine it as one host.) Uru Live has a single public shard -- when you log into Uru, you're in the Uru world, and you can (potentially) meet anyone else logged in at the same time. Other MMO games run many shards, but they're all managed by the same company. (Actually, in the 2004 Uru Prologue, Cyan put up two or three shards for load-balancing reasons.)

I envision my game system being much more heterogenous. I don't like the idea of enforcing one server for everybody, or one player database. I don't even want a single group of people operating the game. This should be an open system. That means anybody can run a shard. Download the software and set it up; you're on.

Shards should be completely independent. We don't want one badly-maintained shard to corrupt others. We also don't want the whole system to die because one person went on vacation. By keeping shards separate, we can keep problems contained. We can also address scaling issues -- crudely but effectively -- by setting up more shards.

Anyhow, there won't be any notion of global avatar progress, because there is no global set of goals or achievements imposed. So there's no real reason to share avatar information between shards.

Naturally, I expect one shard to be the common place where people hang out. There could also be a development shard for the Writers, a testing shard for the Maintainers (or maybe several), and private shards for small groups or for the hell of it.

When you decide to run a shard, you decide what Ages it will contain. This will be a plugin system; you download an Age plugin (Python code) from whoever wrote it, stick it into your server directory, and presto. Some Ages may be used in all shards, others might be featured by a single shard.

There can be a published list of public shards -- I'll accept that much centralization. (It could be as simple as a wiki page.)

Scenario

(This section is, of course, specific to the Uru mythology.)

The Called, exiled from the Cavern, gather on the surface to discuss their future. Their Relto books no longer work; Yeesha has apparently abandoned them. But the Guild of Writers announces a breakthrough: intensive computer analysis has found some of the underlying structure of the D'ni linking symbols. Surface dwellers are beginning to create effective Linking Books.

While the Guild cannot replicate all of Yeesha's techniques, they have discovered some useful tricks. Instancing is one. More important is the ability to replicate linking pages -- literally print them out on an inkjet printer. (This only applies to modern-made Books, not to Relto or D'ni Ages.)

This means you can carry around a sheaf of link-home pages on your belt. When you use one, it remains behind (and disintegrates -- biodegradable!) but you still have the rest of the sheaf. Similarly, if you come across a Book that you want permanent access to, you can lift out a linking page and take it home to your library. As long as the Book's creator included a whole sheaf of pages, the Book won't be damaged, and there will be plenty for future explorers.

Your "home" in this scenario is not a beautiful island Age. It's just a small room in your house or apartment -- a closet that you've converted to an office for your Uru work. Very plain. (You might get to customize the color of the walls.) You have a desk, a bookshelf and a stack of linking sheets. This is your entry point to the shard, but its game function is more like the Nexus than like Relto.

You have a book for a community Age (Ahra Pahts or something like it). You have, or will gather, more books and pages as the shard provides them.

Since all these Ages are written by surface dwellers, we have no access to any D'ni Age we are familiar with. Nor will you find any links to the Cavern, or any other place on Earth besides your home. There may, however, be traces of the D'ni out there in the Ages we explore -- perhaps even other civilizations with linking technology. The Tree has many leaves, and no one knows what the next one might hold.

(This scenario takes a deliberately conservative approach to Cyan's intellectual property. I assume that the people running this game would want Cyan's permission, but would not want Cyan to take an interest in controlling the game world. To get that, I take a long, ostentatious, good-faith step away from their financial interests. Cyan has always hinted that their outlook on player-created Uru content would be "No D'ni history, no D'ni Ages." I can live with that.)

(Of course, if Cyan is cool with us using their toys, that's great. I'd want to at least use the familiar Linking sound effect!)

Storyline: Not Mine

Uru Live wanted to be very story-oriented; much more so than most MMO-RPGs. And Cyan wanted to have firm control over Uru's story. They did not, most people agree, get the balance right. Control versus flexibility versus coherency versus player involvement is a long argument, which I will not reiterate here.

In a fan-run game, I don't think one group should be in control of all the story. That model doesn't even start to work without a lot of community trust of the game-masters -- a different kind of trust than mere technical adequacy. Cyan held that trust tentatively, and (for a lot of players) squandered it. I do not propose to re-vest that trust in another cabal.

Rather, I'll let everyone do their thing. (The Myst logic of many separate Ages encourages this.) If something good emerges, it'll have to emerge on its own. So this section of the plan is up to everybody. Yes, including you.

Architecture Details

Language: Python

Obvious choice. I like Python. Uru's client scripting is Python, so anyone who's played with Age creation so far has at least seen it.

(Security is a weak spot. I will address this later.)

Communication: Jabber

Jabber is a widely-used IM and chat system. Google Talk and Livejournal's chat system are both Jabber.

Using Jabber as the transport layer for a game is a compromise. I'm using it because I'm used to it. I've implemented a board-game system (Volity) using Jabber, and I am writing this plan to work very much the same way.

Basically, the shard server is a Jabber bot. Each Age instance is a Jabber chat room, managed by an instance server, which is also a Jabber bot. Your client is a Jabber client with a fancy graphical display; when you enter an instance, you join that chat room.

Pros:

- Open source. Jabber libraries exist for lots of languages, including Python.

- Supports Unicode from the ground up.

- The Jabber server handles authentication and encryption for us.

- Jabber is firewall-friendly; it only needs an outgoing network connection (to the Jabber server).

- It's a chat system, so game chat is covered. (And it interoperates with every other Jabber chat server. Someone running iChat on a Mac, or Google Talk, could send you a message in-game, same as they talk to anyone else.)

- Jabber is extendable. Sending movement or emote messages through Jabber isn't a gross hack; the format is designed to let people design new message types.

Cons:

- Not as fast as a raw TCP connection. (All messages go through the Jabber server; all messages are XML snippets. Message encoding, transport, and decoding take time.)

- We'd probably want to run our own Jabber server, which is a bit harder to set up than (say) a wiki or an IRC server. (The architecture I'm planning doesn't require customizing a Jabber server; but things are faster if the game servers and the Jabber server are on the same machine.)

A Jabber-based system would not be as speedy as Uru Live. My experience from Volity says that game actions would take a small fraction of a second -- say, 1/4 to 1/2 second. That's fine for board games; it's fine for chat and emotes. But it's a bit slow for a 3D game. (Imagine that fractional delay every time you push a puzzle button.)

More importantly, Jabber is not optimized for many tiny messages. When you walk around in Uru Live, you are sending a constant stream of avatar position updates. My Jabber-based system can't do that. (The XML snippets aren't huge but they're bulkier than a typical MMO walk packet.) So it would send those updates much less frequently. Maybe once every ten seconds, or less often than that. In a crowded instance, the server might have to filter that down even further. Chat, emotes, and action messages would have priority.

Basically, movement of other avatars would look like occasional jumps. You wouldn't get the walking-around that you're used to. You might fail to see someone who just arrived, or see somebody present who really walked away thirty seconds ago. A static conversation -- several people standing in one place talking -- would be fine, though.

As I said, it's a compromise. I think of chat and puzzle-solving as being more important to Uru than smooth animation.

(By the way, when I say movement is jumpy, I'm talking not talking about your movement. Your viewpoint will move smoothly, like in any 3D game.)

(An alternative: you could treat movement updates as a very special case. Don't send them via Jabber; have a separate stream, binary-encoded and UDP. You'd need to treat the UDP data as unreliable, superseded by any Jabber data about that avatar. But I was planning to do something like that anyway. See the "Synchronization" section, below.)

Display: Ogre3D

I typed "open source 3d engine" into Google and Ogre was at the top of the list. It's portable and it supports Python scripting, and that's all I was looking for. If some other package turns out to be better, that's fine too.

Other possibilities: Irrlicht; NeoEngine; Crystal Space.

Note that I have listed 3D graphics engines. I am not considering game engines, MMO engines, or online virtual world systems. I don't want a software package that comes with communication or server code; I'd just have to rip it out.

It may sound stupid to plan to write MMO communications code "from scratch". But it's not really from scratch. Jabber is a complete, working, scalable message system. And the game server code needed for adventure gaming is really not complicated. Jabber bots that talk to a database, and write a limited amount of instance state, should be easier to maintain than a third-party virtual-world system.

(Of course it's perfectly reasonable to plan an Uru game using an existing MMO client-server solution. It's just not this plan. For the sake of completeness, here are some open-source virtual-world projects: Uni-Verse; Croquet; Project Darkstar.)

Age Distribution

An Age consists of two parts: a server module (Python), and an Age package (ZIP file containing textures, 3D models, and Python).

By the way, the Age is identified by a URI (a string), rather than by a sequence number. (URIs are great. Anybody can invent a URI without worrying about collision -- just pick one based on your home domain or email address.)

The server module is downloaded once by the shard admin and installed into his shard config. The module contains the URL of its Age package. (Or the shard admin can specify a mirror URL, I guess, if he doesn't want to rely on the original author's web server.) The URL can be any web address.

There's also a general UI package associated with the shard. This contains clothing, menu images and scripts -- the stuff that the player can see in any Age and instance of the shard. (But note that different shards can offer different UIs. So you might have a standard Uru KI interface on one shard, and an enhanced KI on another.)

When a client logs into a shard, it downloads the UI package; when it links to an Age, it downloads the Age package. These are simple HTTP downloads, using the URLs that the server provides. We use an HTTP HEAD request (or If-Modified-Since) to skip the download if the client already has the package cached.

(Since downloads will be slow, we might offer the player a "download in background" button on the download screen. That effectively cancels the link, and lets him wander around the original Age or go somewhere else while his client finishes the download. We don't really want a "download all Ages" option, because there's no upper limit to the number of Ages on a shard.)

The client caches packages. So it will have to offer a way to clear the cache. Probably just a list, showing the last time each one was loaded, and a button to delete the older ones.

Note that this system is very modular: an Age package must contain every resource used in that Age. This is simple, but not efficient. (If a texture appears in three Ages, you'll download it three times.) I think simplicity is more important to begin with. If resource sharing becomes important, I'd do it by wrapping the shared resources up as a separate package; then the server module requests a list of packages (instead of just one).

Age Upgrades

Ages will change over time. But it's likely that different shards will update them at different times. This means we need a system for tracking different versions.

There are several upgrade scenarios:

- A server module is updated, but it doesn't require any changes to the Age package. (Bug fixes, for example.)

- An Age package is upgraded, but it doesn't require any changes to the server module. (Models or textures are improved with no change to the scripting.)

- A major update requires both the server module and the Age package to change.

The first two cases are pretty simple.

- Distribute a new server module. Shard admins will install it (or not bother) at their leisure. (For simplicity's sake, you have to take down your shard to install new Age modules. Cyan did it, you can do it.)

- Post a new Age package at your distribution URL. The next time a player links in, his client will download it. A player who is currently in your Age won't see the new models right away, but that's okay.

The third case is the tricky one.

- The rule is, if your Age update requires a new Age package, you must change the package URL. And you must leave the original package available -- because some shards might still be running the old version. You should only take down an Age package when you're sure that no shards out there are running the code that requires it.

(The server module and Age packages will each contain embedded version numbers which ensure that this matching is correct. I have a standard scheme for doing this, which I won't get into here. See version matching on the Volity wiki if you really care.)

Logging In and Out

The shard has a shard server, which handles new arrivals, and also shard-wide services such as personal messaging. The shard server, as I said earlier, is a Jabber bot (written in Python). It is always logged into Jabber, and can talk to a MySQL database (the vault).

When you start your client and select an avatar, the client contacts the shard server. The server notes that your avatar has no active game session, so it tells you to link to your "home" instance.

(By the way, Jabber lets you log in with multiple clients at the same time. My game architecture is fine with that. You can drive two avatars around on different shards, or even on the same shard, as long as they're different avatar records.)

When you enter a new instance, the shard server starts up an instance server, which is also a Jabber bot. The instance server creates a Jabber chat room and sends the address back to your client. The client joins the chat room, the instance server sends you the local state (including other avatars), and then you are officially in the instance.

When your client disconnects, your instance server is notified (Jabber handles this automatically). It can then notify other players (in that instance) that you've vanished. (The shard server doesn't have to care that you've logged out.)

Chat and Friends

We rely on the basic Jabber facilities for chat and friends-list. When you speak in an instance, the message goes out to the chat room, and everyone else's client sees it. The instance server isn't involved at all. Similarly, when you send private chat, it's a regular Jabber chat message.

(Emotes are regular Jabber chat messages with a special tag naming the emote. Jabber lets you add special tags to any message. Other clients, like iChat or Google Talk, will just ignore the tags.)

Jabber gives you a friends-list. Whenever you log on, Jabber automatically notifies your friends; again, the instance server (and the shard server) don't have to be involved. Your client will add special tags to your presence notification to indicate which Age you're in.

(This won't work identically to Uru Live. For example, when you friend someone, they have to accept it -- that's a Jabber policy. And we can have a "recent" list, but it won't include the player's Age location, because you only get presence notifications from friends and people in your chat room.)

No Physics

The Uru physics engine is a big old pain in the butt. Way too much of Age development is "find the collision holes; find the improperly climbable walls." Coordinating a rolling object between many players is a significant load on both CPU and network. The heck with all that. No physics. You won't be able to implement Jalak or Eder Gira, exactly. Big deal.

Certain polygons will be marked in the Age file as "floor". Your avatar can move around a floor polygon (strictly two-dimensional movement, no jumping). When you reach the edge of a floor polygon, if there's an adjacent floor polygon in the mesh, you can continue on to it. If not, you stop.

Ladders are "floor" polygons with a vertical orientation. The client doesn't have to treat them specially, except to change your movement animation. Same goes for water. You can't fall through the world because there's no falling. You can't get flung through the ceiling by a misaligned ladder. Everybody is relieved.

(Yes, that ladder flinging thing really does happen with Uru's Plasma engine. Take a look at the Guild of Writers' instructions for ladder placement. Not pleasant.)

Some "floor" polygons trigger scripts. We will get more into this later, but this is how you do a falling or jumping action if you want one in your Age. You mark a specific polygon with a script saying "When the player walks here, move him down to that floor polygon there." (Or panic-link him with a falling animation.)

Limited Avatar Animation

I'm leery of animation because it's unexplored territory. The current Writers group has people working on textures, models, sounds, and scripts, but nobody has touched character animation (as far as I know). So this plan includes only minimal animation work. Stiff walking/running, stiff ladder-climbing, maybe a stiff panic-link move.

I'm assuming that simple animations -- a door opening, a globe rotating, an avatar falling straight down -- will be easy. However, Uru Live currently has a huge palette of fluid avatar animations, for emotes and story actions. I don't think we're going to replicate those, not right off the bat. We're certainly not going to have the perfect finger-on-button, hand-on-rung precision that Uru Live offers.

But I've already conceded that avatar position updates will be slow and jumpy. So weak animations don't really make things worse. You're just going to have to get used to avatars standing around and being stiff.

If someone then comes along and offers better animations, that's great.

Synchronization

This is the hard part of the MMO problem. (It's certainly the part that Uru Live had the most trouble with.) Keeping everybody's world-state in sync is easy, if you don't mind lag; avoiding lag is easy, if you don't mind client inconsistencies. Then your database bogs down, and you have the lag and the inconsistencies.

This scheme is optimized for Myst-style adventure gaming. That means small Ages, with a relatively small amount of persistent data. (Kadish Tolesa has maybe fifty stored values for all its puzzles.) And not too many people interacting with one instance's puzzles at a time.

(If you want gigantic Ages with lots of players interacting with lots of objects, I can't help you. That's a hard problem. Go talk to the people who run Second Life or OpenCroquet.)

The general rule is: the outcome of game actions will be decided by the server. (This is in contrast to Uru Live, which left a lot of decisions to client scripting.) Jabber messages are reliable and in-order, so as long as the server processes commands sequentially, consistency is assured.

This costs. Reliable, in-order messages can be slow; they can bottleneck. So we have to be careful to make server-side decisions quickly.

Therefore, our other general rule is: the instance server keeps all the instance state in memory. It shouldn't hit the vault database every time a door opens or closes. For transient events (like the Delin/Tsogal door opening), it won't hit the database at all. Permanent state changes (like the Bevin book room door opening) will have to be written to the vault, but that can happen as a periodic checkpoint. As much as possible, we want to avoid a player action blocking on server database work.

Nonetheless, when you push a button, there will be a brief pause before you see a result. If the server is stressed, this may be a long brief pause. In general, you will be "stuck" to the button until that server reply comes back. (Although in some cases this won't be necessary.)

This brings up the flip side of game actions: moving around. I've said that this system is pretty sloppy about player location. The client knows where you are, but the server (and other players) aren't updated that often.

"Great," you say, "leave location up to the client." But in many cases, game actions are triggered by location. (For example, the Cleft bridge that breaks when you step on it. Or the Gahreesen auto-doors. Or the Teledahn prison.)

It's easy to mark some "floor" polygons as having (client) scripts, so that stepping on them has an effect. But I just said that game actions suffer a brief pause, while the server replies with the result. Should you be beset by these pauses while you walk around an Age? I think not. Free movement is a big part of the immersive experience, and it's worth making an exception to keep it smooth.

The problem is, if you don't freeze when you enter a script region, you run the risk of "outrunning the script". (You start to run across the Cleft bridge. The server is running slow, and by the time it reacts, you've already reached the other side. Whoops! Now you're somewhere impossible. Not a big deal in the Cleft, but it could be a plot bug in another Age.)

To prevent this, we give these regions a "sticky" attribute. When you enter or leave a sticky region, the client sends a location update to the server. (The client does this regularly, of course, but it is careful to send one when it crosses a sticky boundary.)

Until the server acknowledges this update, you are logically stuck to the region. As far as the client is concerned, you're frozen. You can still move your avatar around, but you can't push buttons or trigger any other scripts.

Hopefully, this hidden freeze will be brief (a quarter second, just like being stuck on a button). Then the server reply comes back, and everything continues on; you never ever notice it's happened.

But say the server replies "Hey! The bridge just broke!" As far as the server is concerned, you were on the bridge when it broke. Game logic decrees that you must fall. So the client runs the "break and fall" event -- regardless of where you were. You teleport back to where you're "supposed" to be (the break-point of the bridge).

Again, in the normal case, it's only been a quarter second since you hit the bridge. Falling makes sense. But if the server is slow? Well, you might be teleported back several steps. Maybe even from the far side of the bridge. Too bad. Adventure game design needs reliable plot logic.

(Mind you, not every script region requires this kind of rigid control. If a room's lights brighten as you enter, that's just cosmetic; it's no big deal if it's out of sync with your "real" entering time. So that region wouldn't be marked sticky.)

There are more details to this plan. (What if you enter another sticky region while logically frozen? What if you fall off a cliff? What if you log out?) I won't go into them, because this section is already way too long.

Potential Problems

Scaling Issues

I've said that I'm willing to accept less scalability than Uru Live had. That doesn't mean I want to ignore the issue entirely. There are several walls that Uru Live ran into, and we should at least think about them.

Really large Ages: We'd like to support areas which are very large, but are divided into sections. The client doesn't render distant sections, thus saving polygons. (UL does this in Aegura. If you haven't noticed, it's because it does it well.) The 3D engine should support this out of the box; it's an old trick. Hopefully, it'll be easier than the Plasma engine's "multiple page" trick -- I understand that's kind of a hack.

Too many avatars: Even in a simple Age, if enough avatars show up, the 3D engine will eventually choke. The crude solution is avatar pop-in: the client only renders the fifty closest avatars to you. (Once again, we shovel all the graphical problems onto avatars.) A less crude solution (which UL employed) is levels-of-detail on the avatar models.

Client threading: Uru Live had a lot of problems where the client's Python scripting would hold up the Plasma rendering. (That is, some network traffic would arrive and cause a frame-rate glitch.) I haven't looked at the Python-Ogre interface, but I really hope we can avoid that. It will require careful implementation of the interface. I expect this to be the hardest part of the whole system, really.

Instance server overload: The biggest traffic load on the instance server is avatar movement updates. (Recall that chat, emotes, and Age-location are handled by Jabber directly.) In a crowded Age, the server will have to start ignoring movement updates. (Not the important scripted ones, but the normal step-by-step updates.) Jumpiness will get worse. We might even need a signal to tell the client to send fewer movement updates.

Vault database overload: All persistent updates in a shard are going to a single SQL database. (I am not smart enough to design a distributed database cluster. I can install MySQL.) My only plan is: don't create Ages which require lots of data written frequently. Keep everything in memory. Checkpoint occasionally; if possible, checkpoint only the state which has changed. (But you have to be careful to keep the in-DB state of an instance consistent.) If problem remains, bring up another shard somewhere.

Not Being MMO Enough

When I posted the first draft of this essay, the most common response was: "Jabber? Slow? XML? You can't run an online game like that! You have to compress movement updates into individual bits!"

Well, small UDP packets, anyway.

As I've said, this is a compromise strategy. Jabber buys you a lot: good authentication and encryption is not easy! And it costs a lot. But I'm not just making a quid-pro-quo argument. I'm trying to pick out what's actually vital to an MMO adventure game, and what people are simply used to.

Free-ranging, real-time movement is a recent addition to the adventure world. Myst 1 through 4 used discrete movement -- click on a location to jump there. Most adventures still work that way, although a handful (including Myst 5) have followed the Uru model.

Adventure interactions require you to be in particular locations at particular times -- the times when you interact. (With puzzles or with other players, it's the same constraint. Although other players are more flexible, since you can generally interact with them anywhere.) In between interactions is essentially gravy. Important, immersive gravy; it's when you absorb the game world. But in terms of what you do, the game doesn't care whether you're looking around at fixed angles, or turning in place, or moving freely. (Not until you enter one of those scripted regions!)

Uru players are used to the MMO model, where every avatar in view seems to move freely. (With occasional glitches; but then, Uru has much better movement animation than most MMOs.) But I'll note that not all adventure gamers are convinced. One of my friends tried Uru and then told me that he wanted a "click to jump" interface. The 3D movement repelled him; he hated maneuvering towards the button or lever or whatever he had his eye on. He just wanted to decide to be there.

That's not how I feel; I like free navigation, and so I've written this proposal to have it. But we should remember that there is no unassailable requirement for this stuff. You could take my plan and drop the free movement entirely; build the game engine to render a series of still views, with other avatars clustered in nice natural-looking groups around their respective location points. It would still be an MMO adventure game. (And you'd be able to drop the section about the sticky regions. I mean, eww. And I wrote it.)

Security Issues

Python is great in many ways, but one thing it's bad at is secure operation of downloaded scripts. That is, when you're getting arbitrary Python code off the Net -- like in an Age package -- you're trusting it completely. There's no way to run that code in a secure sandbox. A malicious Age script can very easily erase your hard drive, or install a virus.

(Old versions of Python contained a "rexec" module which was supposed to offer sandboxing. This is now deprecated, because it doesn't work -- Python actually got too powerful for it. There is also a secure-Python project I've seen, but I don't know if it's been verified or tested at all. I'm keeping an eye on it for possible future use.)

We can't ignore this issue. Anyone who downloads a free game and runs it is trusting the programmer; but this system is an extendable game, and it's intentionally as open as possible. We want a flood of new Ages -- we can't ask the user to trust everybody who contributes to that flood.

We're going to have to start by manually inspecting Age scripts as they are contributed. Ideally, we'd have one "safe" shard -- the common one, to which new players are directed first -- whose admin guarantees:

- that the Age packages that it links to have been inspected for booby-traps;

- that these Age packages are stored on the shard's own web server. (If the Age package is stored on the original author's server, a malicious author could "upgrade" the file at that URL at any time, adding a booby-trap.)

(The admin will also want to inspect the Python server module, but that's for his own protection, not for the players.)

This is additional headache and bureaucracy, which sucks. Development shards, testing shards, and private shards will certainly take a more freewheeling approach, which means we'll have to educate users about the dangers. That sucks too.

The up side is that inspecting Age packages should not be slow or difficult. Normal Age script code will be simple; it will call almost nothing except standard game APIs. If a script calls open(), socket(), or most general Python library APIs, something is wrong. If a script is obfuscated, something is wrong.

Conclusion

It's possible.

Tags: game design, mmos, myst, programming, uru.

Continuing the subject of competitions, I learn from David Swift's blog not only about the existence of the Experimental Gameplay Project, but the fact that several of the games are now on sale in the US at Target stores, paired with thematically appropriate T-Shirts, for $12 each. Wow!

The EGP is an open-ended challenge for computer game developers to - working alone - create a game in seven days or fewer, and the game must show off a central play mechanic that hasn't quite been seen before.

(I grumble a bit that, throughout the website, "game" is understood to mean "digital game" and further understood to mean "game for computers running Windows". But only a bit, coz it's a great concept. And it's not like I don't have a copy of VMWare on my MacBook, for situations such as these...)

Hello Gameshelf viewers! I'm Doug Orleans, Friend of the Show. I have not actually appeared in any episodes, but my copy of Acquire was in Episode #6. I was also mentioned by name because a game I designed, Pylon, was the winner of the Summer 2007 Icehouse Game Design Competition. The IGDC is the topic of this, my first post to the Gameshelf weblog.

The Icehouse Game Design Competition was started by the Icehouse mailing list community in 2004 as a way to encourage people to design (and play, and give feedback on) new games using Icehouse pyramids. It was inspired by similar game design competitions run by the Piecepack and Interactive Fiction communities, which had been pretty successful in generating and maintaining interest in creating new games. I don't remember who actually suggested the IGDC first (the mailing list was not archived back then) but the Gameshelf weblog's own Andrew "Zarf" Plotkin got the ball rolling by serving as the first competition administrator. Zarf ran the first four competitions; in 2005, the fifth competition was run by Jonathan Leistiko, but it was abandoned and the votes were never released.

After a couple years of apparent non-interest, the IGDC was revived in 2007 by David Artman, who ran the sixth and seventh competitions. The eighth competition was recently announced by the new administrator, Dale Sheldon; game submissions will be accepted until June 20th, 2008, which will be followed by a one-month open judging process in which anyone can vote on the games by ranking them all from best to worst. If you want to try your hand at designing an Icehouse game for the competition, create a page for the game rules on the Icehouse Games Wiki and send mail to IGDC.Coordinator@gmail.com. (But first you should read the full competition rules.)

One of the main goals of the competition was to encourage people to give feedback to game designers about their games. To that end, I am going to post my thoughts here about the games in the Winter 2008 competition. I did manage to play all 8 games, but most of them only once, so take my opinions with a grain of salt. I'll discuss them in the same order I ranked them on my ballot, from best to worst, along with my ratings on the Boardgamegeek.com 10-point scale (10 being "outstanding", 1 being "clearly broken").

Virus Fight - 8. The old programming game Core War involves writing computer programs that run in a shared memory space and attack each other by overwriting each other's code. Translating this idea to a turn-based strategy board game turns out to work surprisingly well! Each pyramid represents an instruction based on its color: yellow is "move", green is "write", blue is "jump", and red is "erase". Each player has a program counter, a small pyramid that moves around the board executing instructions one at a time. Unlike Core War, which is completely deterministic after the initial selection of programs, in Virus Fight the players have choices of how to execute the current instruction; for example, a "write" instruction lets the current player place any spare instruction onto any empty square. A player can also choose where to move his program counter after executing an instruction, using the two-dimensional nature of the board instead of the linear memory model of Core War. Despite these differences, much of the spirit of Core War is still here: players' programs start out in separate regions of the board, but can move and expand and merge with each other, allowing players to invade each other by moving their program counters into each other's programs, and the "erase" instruction allows players to remove certain instructions from the board, reducing the other players' options. The goal is to force all your opponents' programs to die by having nowhere to move their program counters.

Aside from the initial simultaneous selection of programs, there is no element of chance in Virus Fight, and when played as a two-player game (which I think is the best way to play, in order to avoid the negotiation and king-making that can occur in multi-player games with no chance) this is a pure abstract strategy game akin to chess or go. I can appreciate most pure strategy games for their elegant mechanics, but in general I don't actually enjoy playing them—I don't have the patience to mentally search the game tree looking for the optimal move. For some reason, though, I really enjoy playing Virus Fight. Maybe it's because it's quite difficult to look more than a couple moves ahead, due to the way the turn order can change based on the relative sizes of the pyramids currently under the program counters, so you have to just play by intuition most of the time. Or maybe it's just that, as a programmer by vocation and avocation, the theme is a natural fit for me. In any case, the game works well, both as a well-balanced strategy game and in capturing the essence of Core War, and for me it was clearly the best game of the competition. Sadly, it did not fare well in the voting, perhaps due to its somewhat intimidatingly complex rules (which are nonetheless quite elegant, in my opinion). But if you like pure abstract strategy games, or programming, give it a try.

WreckTangle - 5. It's very difficult to design a simple abstract board game that has an element of chance without the chance element overwhelming the strategy. Backgammon is the canonical example of this kind of game, and I think it succeeds in part because the chance element only serves to randomly restrict your options at the beginning of your turn rather than to randomly determine if you succeed or fail after performing some game action (like in most wargames). (This distinction is sometimes referred to as "situational luck" vs. "resolution luck"; I can't find a citation for who came up with these terms, but I think I first saw them in The Games Journal.) WreckTangle uses the same idea: on your turn, roll the die (a Treehouse die), then make two moves, one of which is partially determined by the die roll; for example, "dig" lets you move a pyramid, either yours or an opponent's, one space diagonally away from its home row, and this can be done either before or after you move one of your own pyramids. This system works out pretty well: you still have a wealth of options on your turn, but sometimes you have to play the odds and hope that the next player's roll doesn't let him ruin you. This sort of blurs the distinction between the two kinds of luck, however, since these situations can feel more like you're randomly succeeding or failing, especially because, unlike in backgammon, your captured pieces are permanently removed from the game. And a single capturing move (by forming a rectangle—of any size—with four of your pyramids) can capture multiple pyramids, so this can be pretty drastic. Still, I liked the basic idea of WreckTangle, and maybe with some sort of tweak to reduce the potential for drastic swings of fate this could become a solid game.

Hunt - 5. Hunt involves moving a stack of pyramids around a maze of dangerous obstacles, trying to stay alive while positioning the obstacles to kill your opponents' stacks. This game is in the same general class as Wrecktangle, and most of what I wrote about that game applies to Hunt as well—Hunt has slightly less chance of a drastic swing of fate, because sometimes the damage to your stack can be healed, but it also has slightly more of the feel of resolution luck: sometimes your die roll dictates that your stack immediately take damage because you can't make the required move. Fortunately, your stack is immune to damage caused by obstacle pyramids of the same color as the top pyramid in your stack; each time do you take damage, though, you remove the top pyramid of your stack, which means you become immune to a different set of obstacles. There are also ways in which the order of the pyramids in your stack can change, which also changes your immunity. This is a clever mechanism, leading to some tactical positioning options, but you still don't have quite enough control over the element of chance to implement any kind of long-term (or even medium-term) strategy. The rules also seem to be a bit more convoluted than they need to be, which is why I decided to rank this slightly lower than WreckTangle.

Martian 12s - 5. A push-your-luck gambling game, like Blackjack with a few twists: there are essentially three different "decks", and you can choose which one to draw from; also, "card"-counting is not discouraged! This game is simple and to the point, and it works perfectly well for what it is, but it just doesn't excite me at all. I'm not a big fan of push-your-luck games, but that isn't really my problem with Martian 12s; it seems like there isn't much else going on besides calculating the odds and deciding the appropriate level of risk to take. This turned out to be the winner of the competition, which I'm okay with—I would have preferred Virus Fight, but Martian 12s is a solid game that works as intended, and that's really the main goal of game design, isn't it?

Timelock - 3. Here we start getting into the games that had serious problems. Timelock is structurally quite similar to backgammon: your dice roll determines how far you can move your pieces towards the goal, and you can sometimes interfere with your opponent's progress. The problem is granularity: in backgammon, rolling high numbers is generally better, since you can make further progress towards your goal, but sometimes you want a specific smaller number so that you can land on a particular spot; in Timelock, however, rolling higher numers is always better, and for the most part it's simply a matter of who rolls the highest total over the course of the game. There are some slightly non-linear decisions about whether to make progress towards your goal or to block (or undo) your opponent's progress, and some Treehouse die results are better in some situations than others. But most of these decisions are obvious, and there's really not enough of this non-linearity to matter, so it pretty much boils down to a dice-rolling contest.

Timberland - 3. This hybrid of Treehouse and Volcano seemed like it had promise, but turns out to be overwhelmingly random—even moreso than Treehouse, which aims to be the Fluxx of Icehouse games. Volcano is a Nim-style game, where all the pieces on the board are shared between the players and you're trying to arrange for the best captures to be available on your turn. But when you add the randomness of rolling two Treehouse dice on each turn, it's pretty much impossible to arrange a configuration that will have any chance of surviving until your turn, even in a 2-player game; it's difficult just to minimize the next player's chances of making a capture on his turn, even if your options weren't restricted by what you rolled. In theory, I like the idea of adding an element of chance to Volcano, but this isn't the way to do it.

Chicken Run - 2. This game is similar to Timelock (and backgammon), but it has the same problem: higher rolls are always better. In fact, you only get to move at all if you roll higher than your opponent, which makes it boil down to a series of dice-offs, rather like War. The only interaction comes from moving neutral pyramids to block your opponent or unblock yourself, but they can only be moved if both players roll the same number, which only happens one sixth of the time on average. This means they play a very small part in the game, and in fact the first time I played I think we only got matching rolls once before the game was over. I won't go so far as to say this game is broken, but it would need some significant changes before it would really work.

Martian Gunslinger - 2. There are some interesting ideas in here, sort of a resource management/exploration/dueling card game with an intricate Western theme (...on Mars). The problem, once again, is the overwhelming amount of luck, especially resolution luck: when you "attempt a plotpoint", you draw two cards, and you succeed only if the first is higher than the second. Also, it feels like an afterthought that this game involves Icehouse pyramids at all: one part of the rules suggests using them to keep score, encoding numbers based on stacking configurations, while another part talks about using dice to keep score. (There are pyramids on the board as well, but these could just as easily be pawns, or painted miniatures.) The rules are also ridiculously complicated, with each playing card representing a different action, resource, and event, based on three lookup tables filled with text descriptions of what they do. Even if this were a custom deck of cards, there probably wouldn't be room on most of the cards for the explanatory text! There might be the germs of a decent game buried in here, but it's probably not an Icehouse game.

Amazing video of a quadruped robot, the "BigDog", created by Boston Dynamics. It can carry up to 340 pounds of pack-weight, and immediately reminded me of the title character from M.U.L.E.

Tags: adaptations, MULE, robots, videos, youtube.

I keep meaning to post a long post all about how cool Strange Synergy is, but here's just a little post right now.

One of the things I really like about Strange Synergy is the game-design aspect. In the beginning, you are randomly dealt a number of power cards (things like "Zorch Ball" and "Mental Crush" and "Smoke Bombs" and "Rubber Body"), and you have to assign those powers to your team of three characters. The rules say that you get nine cards and give three to each character, but I've found that I like giving each player fifteen cards, of which they get to give three to each character. This has a few benefits, one of which is evening things out a little bit, as you can sometimes get stuck with a really crappy set of cards and get completely dominated by another player with better cards.

The other benefit is that you actually get to feel like you're doing a bit of game design before you play the game. You get to decide what your characters' powers are, figure out which combinations will work best, how each character will complement the rest of the team, etc. And then you get to test out your design by actually playing the game.

I would like to find more of these kinds of games, where there is a design element incorporated into the game. If there are enough interesting ones, I kind of hope that I can suggest that these all be pulled together as a theme for a future Gameshelf episode.

So, anyone have suggestions for other games to add to this list?

Tags: game design, games, strange synergy, the gameshelf.

Joseph Weizenbaum, who created ELIZA in 1966, died earlier this month at the age of 85. Across the internet, many were the impromptu memorials formatted as dialogues with the landmark software. (And how does that make you feel...?)

Eliza is more of a toy than a game, but it's perhaps the first widely seen use of a computer program masquerading as a human. It no doubt got a lot of people thinking, despite how thin that particular mask was. Allow me to assert that the text adventure games that would start to appear ten years later were descendants of ELIZA, and so therefore is much of the modern digital game landscape.

(Much less significantly, I once wrote a Perl script that had Eliza analyze the "Jeeves" persona of askjeeves.com (which is now ask.com), and put a transcript of their session on my website.)

But as my friends and Gameshelf watchers already know (because I never shut up about it), text-based games continue to live on, like Neanderthals among the Homo Sapiens. Except these are the crafty sort of Neanderthals who moved underground, refusing to become an evolutionary cul-de-sac, quietly carving out obscure empires largely unknown to the surface-dwellers in their shining cities and their Half Life 2 game engines.

Um. My point is that the 2007 XYZZY Awards happened this month and Admiral Jota's entirely charming Lost Pig, chronicling an unusual adventure in the life of an orcish peon, took top prize. I played this game last year and enjoyed it a great deal. You should play it too.

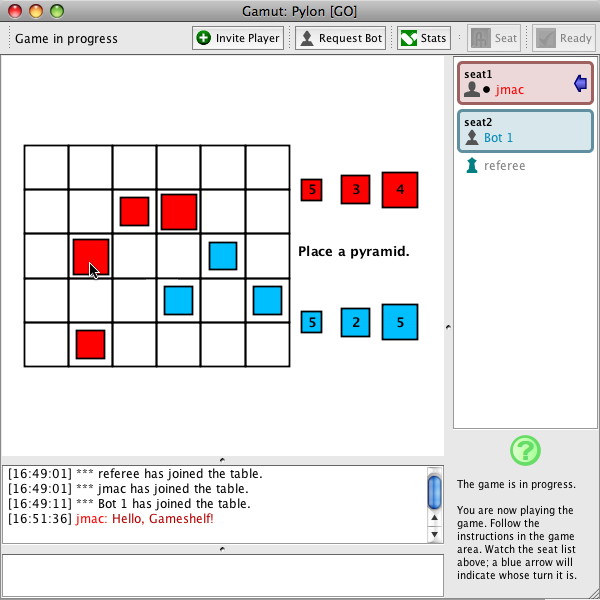

Doug Orleans' Pylon, winner of the 2007 Icehouse Game Design Competition as reported in Episode 6, is now an online game! It's hosted on the Volity Network, with art and programming by Doug himself. The user interface is rather basic but entirely functional, and the game's playable against both human and automated opponents. Give it a try!

Doug Orleans' Pylon, winner of the 2007 Icehouse Game Design Competition as reported in Episode 6, is now an online game! It's hosted on the Volity Network, with art and programming by Doug himself. The user interface is rather basic but entirely functional, and the game's playable against both human and automated opponents. Give it a try!

(Special insider Gameshelf trivia: I referred to Doug as "Somerville's own" during that show, even though he had moved to Billerica, several towns away, by then. But I figured that he probably at least started to think about the game that would become Pylon while he still lived here, so it was all good.)

Some unrelated notes, while I'm here:

I discovered a couple of days ago that the spam-fighting features of this blog were wound a bit too tightly, and perfectly legitimate comments were getting treated as junk. If you got a message that your comment was being held for moderation, but you never saw it appear even days later, please accept my apologies! All such comments have been promoted to their rightful, visible status now, and I've tweaked the blog's spam-fighting settings to act a bit more lenient. Please let me know if you sense anything fishy going on in the future.

In happier news, I'm pleased to announce that production has begun on our first couple of new episodes for 2008. These shows will be different from those that came before, in several ways. We're trying new things with the format, and we're also shooting footage for more than one episode at once, which I will later edit into separate half-hour shows; this is my attempt to complete more than two shows per year. It's gonna be the best year yet for The Gameshelf, and we're happy to have you watching!

A couple more quick links from the Internet, where "the Internet" in this case means "Chad Orzel's blog". (No particular reason; it just happens to be the place where I saw both of these.)

Susan Beckhardt gives a nice introduction to game theory. If you have no idea what I mean by game theory, or how you can think about games mathematically, read these. If the idea is old hat to you, go play a game or something. It's a quick link!

- The basic idea of game theory, using everyone's favorite example, Nim. (Or actually not -- it's a simpler subtraction game which she calls "G(6,3)". But you think about it the same way.)

Game Trees and Totally Finite Games

- How to analyze a simple game. (This is what people mean when they say things like Checkers is Solved.) Now, what is Supergame?

Third part to arrive after her thesis is turned in. Hopefully she'll give a description of the Supergame paradox, which I remember fondly from old Martin Gardner logic books.

And, in the "old standards" category: Relativistic Asteroids. (Java applet.)

Try the classic version, hit "S" to start the game, and then "F" to put the display in the ship's reference frame. (That's with the ship always in the center of the screen.) Accelerate around and watch Lorenz-Fitzgerald contraction in... action.

I apologize. Couldn't find any other way to end that sentence. I'll go get into the crate now.

Tags: asteroids, game theory, hypergame paradox, physics, quick links.

I don't have Super Smash Bros. Brawl, but I do have ClayFighter 63 1/3 for the Nintendo 64, a game that feels like Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter and Killer Instinct mixed with clay and Ren & Stimpy.

There's some interesting speculation behind why they used the suffix of 63 1/3 instead of the number 64. The obvious guess being that it is making fun of the clichéd 64 slapped on the end of many game titles. The other is a rumor that Interplay was running out of time and that Nintendo kept rushing them without giving any extra time, so the 63 1/3 would seem to be a message this game could have been much bigger and better if it had spent more time in development.

There is no story whatsoever. The player simply chooses a character and fights to the top. It's simple, straightforward and doesn't force anyone to remember any character backgrounds such as "this guy killed my father" or "I want to be the best of the best to prove that my family is the greatest!"

All the character sprites and animation were made using photographs of clay models. It went for that funny cartoony, surrealist style for the characters and made the characters look very unique. Even though the sprites are two-dimensional, the levels which the fights would take place were completely 3D. This is one of the many things that madeClayFighter stand out in the first place. Other games did not even dare to try this approach.

As the fighters move closer or further away from each other, the camera would rotate around to show that this isn't just a sidescrolling level. Both characters can move around in a circle if they keep moving left or right. This is only the point in the level where neither character can pass. It is at this point, an opponent can smash the opponent with a strong attack then end up at another section of the level that isn't normally seen. This would usually be the roof of the level, inside a castle, or inside a sewer. The player can even knock the opponent back to the previous part of the level if they get cornered again.

There are 12 playable characters, with 3 of them being unlockable. Interesting enough, there are 2 characters that people may be familiar with who aren't ClayFighter-exclusive characters: Boogerman and Earthworm Jim who both had their own games on the Sega Genesis, which the previous ClayFighter games were initially made for. Even though there are no character stats that show which ones are stonger, faster or jump higher, the character that is chosen is pretty much a matter of preference. I always let the game choose randomly for me by holding the L+R triggers together. The 3 hidden characters can be chosen after pressing the right key combination at the character selection screen. Each character has unique animations and sound effects for every attack and damage taken. You will hear things suck as "cluck you", "quit it", "I will destroy you", "I told you I'd win" and even "you suck". It never gets annoying.

In addition to the quirky characters, there is also a combo and fatality system reminiscent of serious games such as Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter and Killer Instinct. At the beginning of every match, the narrator would shout "Let's get ready to crumble", which is aspinoff of Michael Buffer's catchphrase "Let's get ready to rumble". When the blue power meter is full, the player can pull off a combo that will set off into crazy combos causing the announcer to shout things such as "itty bitty combo", "tripple brown betty combo", "insane combo" and even "little girly combo". These combos can consist of landing 3 to even 400 hits (that's right, 400) and up depending on how high the meter is and how close you are to the opponent. When either player loses their health completely, they kneel to the ground waiting to be taken down with one hit or with a fatality, whichClayFighter refers to as a claytality. These claytalaties can range from throwing them in the air flying up from the island they're on hitting the camera as if they were going to fly out of the TV, being blasted in a cannon and even being chopped in half! The word "CLAYTALITY" would appear in big bloody letters.

The controls were great. It utilized the obvious A and B buttons, and the C buttons were each used for attacking as well. The L+R triggers would be used to step sideways, which is useful to dodge projectiles, but I barely used it since I can jump over most attacks and I fought just fine without them. At low difficulties,ClayFighter 63 1/3 is a crazy button mashers, and at the "PSYCHO" difficulty, the computer will grab you and unleash 10-hit combos of their own. There are 5 difficulties altogether: Cookie, normal, whoa, dude and psycho.

It also allows two players to fight against each other. It is a simple one-on-one versus mode. It's been years since I've actually played against another person, so I can't say too much about this.

With all the jokes, funny characters, and slapstick sound effects, ClayFighter 63 1/3 still feels like an unfinished game. There is no save option anywhere, so any unlocked characters and victories will never be recorded. Once the N64 is turned off, the player is forced to start all over every time. The character movements are slower compared to other fighters such as Super Smash Bros. and Killer Instinct. A sequel was made as a blockbuster-exclusive rental,ClayFighter Sculptor's Cut and it suffered the same problems as 63 1/3. The fact that Sculptor's Cut could only be rented from blockbuster and not purchased made it appeal to an even smaller audience. To make matters worse, the developers of ClayFighter 63 1/3, Interplay shut down in 2004 due to financial problems, making it seem highly unlikely that a new ClayFighter will ever emerge. Since Interplay owns the rights to the game, it will may never appear on Nintendo's beloved Virtual Console or even as a Nintendo DS remake. When ClayFighter first came out for the Sega Genesis, it was a childish fighter that took place in a carnival after a radioactive comet crashed. On the N64, it evolved into a funny game that paid homage to the fighting giants Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter and Killer Instinct through parodies in gameplay mechanics. It appealed to an older audience and toned the violence down enough to make it youth-friendly at the same time. It is a real shame that it never skyrocketed into popularity with its visual style and the strangeness of the characters themselves.

The button-mashing style of play at the lowest difficulty was always my favorite and I loved pushing the opponent to different parts of the level and then finishing them off. The crazy clay characters and the parodies of other fighting games appealed to me and is a nice between a combo-crunching fistfight and being just plain weird. The lack of a story took nothing away from the game quality. The camera is always smooth and never obstructed my view. If Interplay ever gets back on their feet and starts making games again, I would beg them to work on ClayFighter somehow. It's been 11 years, and I can't think of anyone else who's made a decent fighter game that has a crazy style of humor that feels similar to other games mixed with clay and insanity. With the cartoon visuals of Team Fortress 2, Battlefield Heroes and Zack & Wiki, I can't see a reason why they can't make their own in-house visual rendering technology that can make 3D models look like clay. ClayFighter is one of those games that died too early in its infancy and needed more time to grow. It dared to go in the opposite direction while other fighting games became more complicated with higher-quality graphics and near-clunky controls.

Tags: clayfighter, games, N64, nostalgia, reviews.

A few months ago I played Penumbra: Overture, and wrote:

A survival horror game. I'm not sure why it's marketed as adventure. Perhaps because the technology isn't up to commercial survival horror games; the graphics are crude, the controls are clumsy, and there are only a couple types of creepy-crawlies.

The gimmick is a physics engine, on which some of the puzzles are based. Sadly, this is bad for the puzzles -- I spent a lot of time trying ideas which should have worked, but which I couldn't force the physics to comply with. And it's not great for the horror either. Rule of thumb: simulation engines lead to solutions which are emergent, surprising, and dull. You can kill nearly everything in the game by kneeling on a crate and flailing with your biggest weapon.

(from my web site.)

This week I played the sequel (and conclusion), Penumbra: Black Plague, and wrote:

This chapter fixes everything I complained about in the first game. The physics engine is now harnessed to serve the puzzles and plot, instead of the other way around. You still do lots of stuff, but your actions are now clear and definite when they need to be, analogue and simulation-y only when that's interesting. The combat is entirely gone; monsters may chase you, and you might even be trapped in a room with one, but you aren't flailing with a crowbar. You have to either run, or figure out how to use the environment to save your butt. More immersive, scarier, and far less dull.

Is this not interesting? ("You mean the way you reflog stuff from your website onto the Gameshelf?" Thanks, Steve, back in the crate please. We're doing Analysis, here.)

The interesting point, at least to me, is that the designers turned a mediocre action game into a good adventure game by taking things out. They took out the periodic attacks by zombie dogs. They took out the succession of weapons (broom, crowbar, hatchet). And they took the physics modelling out of many (but not all) of the story actions you undertake.

When we ask "what kind of game is this, really?" we expect the answer to be: whatever you spend most of your time doing. Overture had plenty of adventure-style puzzles and unique story actions. But they were paced out with zombie dogs. Furthermore, when you were wandering around exploring, you were watching for zombie dogs. (Which answers a slightly deeper question: what do you spend most of your attention on, in this game?) So Overture felt like an action game punctuated by adventure puzzles. Particularly since the action parts were flawed, and thus memorable. (Sorry! That's usually the way it works in reviewerland.)

("Survival horror" has a bit of cognitive advantage in this comparison. It's a subgenre of "action game"; but "action" these days implies some adventure-style elements -- if there's any storyline at all -- which there usually is. Action games will have some puzzles, some environment interactions, that sort of thing. Certainly all the well-known horror lines -- Fatal Frame, Silent Hill, etc -- have these adventure elements. Whereas adventure games are quite allergic to action-style intrusions. When minigames show up, as in Next Life, or even jumping sequences as in Uru, many adventure gamers mutter darkly and wave incense.)

Now, I'm not saying that the improvements in Black Plague, the sequel, stemmed only from negative changes. I fully acknowledge that the designers put in good stuff. They were able to do this -- and, moreover, make that good stuff dominate the game -- by dropping the elements that hadn't worked before.