Category Archives: Best Of

Last semester I found myself needing two copies of Xbox Left 4 Dead so that we could study that game in class. I already owned one, and feeling too lazy to requisition another from the university, I arranged a temporary trade for a friend’s copy. He requested Dark Souls in exchange, having observed my copious tweeting on that topic a few weeks before. The semester’s over now, and my friend had quickly found that Dark Souls wasn’t really his cup of tea. I’ll propose a lunch to reverse the exchange sometime, but I’m in no particular hurry: I don’t really want to see Dark Souls in my house again, let alone in my game console.

Last semester I found myself needing two copies of Xbox Left 4 Dead so that we could study that game in class. I already owned one, and feeling too lazy to requisition another from the university, I arranged a temporary trade for a friend’s copy. He requested Dark Souls in exchange, having observed my copious tweeting on that topic a few weeks before. The semester’s over now, and my friend had quickly found that Dark Souls wasn’t really his cup of tea. I’ll propose a lunch to reverse the exchange sometime, but I’m in no particular hurry: I don’t really want to see Dark Souls in my house again, let alone in my game console.

To say I don’t like the game would be an oversimplification bordering on falsehood; in fact, the game brought me many hours of enjoyment, and I carry lasting fond memories of certain gameplay moments. As reports from friends filter in that they are finally finishing the game (it takes upwards of 100 hours to traverse), I think back to these moments, and the chance that I’ll give it another look someday rises above absolute zero. But this can’t happen in the near future: my relationship with this game ended so disastrously that it’s really better for both of us to avoid contact for a long time.

I must risk sounding melodramatic to explain why this game so profoundly unsettled me: I had never felt such purely negative emotion about a videogame in my adult life as I did at the moment when Dark Souls betrayed my trust.

Tags: dark souls, digital games, jmac on games.

Near the beginning of David Sudnow’s Pilgrim in the Microworld, published in 1983, the author, a Berkeley-based sociologist and polymath, describes his discovery of the Atari VCS at a friend’s party. Missile Command in particular intrigued him so much that he immediately visited a store to buy his own console. That game was out of stock, but the salesperson recommended Breakout instead. He proceeded to play that game obsessively for three months, and then wrote a 160-page book about it. The resulting artifact was unique for its time and remains an unusual work; even as the field of games criticism grows deeper and richer, this book from the previous century has something to teach us.

Near the beginning of David Sudnow’s Pilgrim in the Microworld, published in 1983, the author, a Berkeley-based sociologist and polymath, describes his discovery of the Atari VCS at a friend’s party. Missile Command in particular intrigued him so much that he immediately visited a store to buy his own console. That game was out of stock, but the salesperson recommended Breakout instead. He proceeded to play that game obsessively for three months, and then wrote a 160-page book about it. The resulting artifact was unique for its time and remains an unusual work; even as the field of games criticism grows deeper and richer, this book from the previous century has something to teach us.

This image is one of the ads that has been flitting across my Steam dashboard lately. It depicts two characters from Half Life 2, paired with the blurb “The best game ever made”, attributed to PC Gamer magazine. And it, alone, provides an excellent summary of why I don’t read game reviews very much.

This image is one of the ads that has been flitting across my Steam dashboard lately. It depicts two characters from Half Life 2, paired with the blurb “The best game ever made”, attributed to PC Gamer magazine. And it, alone, provides an excellent summary of why I don’t read game reviews very much.

This saddens me, becuase I would in fact love to regularly read a videogame reviewer or two, the way I follow a small group of film critics whose voice I’ve come to understand and trust over the years. My favorite film reviewers are sources of continual education and enrichment, not just about the work on the table, but about the medium and its history as a whole. But I find the field of videogame reviews so choked with the sorts of writers able to produce blurbs like the one in this advertisement that it’s very hard to find any other kind.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can confidently say that Half Life 2 does in fact represent groundbreaking work that anyone interested in the medium and its history should study — as discussed here before, it’s part of the canon. But neither HL2 nor its potential audience is well served by a ridiculous blurb like the one in that ad. If I heard someone say “This is the greatest book ever written”, I would assume that they were a religious person showing obligatory praise for their faith’s holy scripture. And even then, that person is not extolling the book’s literary merit, but rather its utility for spiritual improvement, or some other quality generally inaccessible to others.

That Valve can, six years later [1], continue to hold up this blurb with neither embarrassment nor (as far as I can tell) irony shows the much sadder fact: Both in 2004 and today, this kind of language is normal and expected from videogame reviewers. And that sentiment is, sadly, hard to prove wrong. And so you have tragic situations where a poor soul like me has no firm idea if, say, Alan Wake is worth the significant time-and-money investment to obtain and play through. I have no writer or publication that I can turn to with reasonable expectation of finding a review with an ounce of perspective.

To clarify: my dilemma more involves studio-produced, retail-sold works. More humble, independently produced games seem to be better served here. Sites like Jay Is Games and Play This Thing feature daily reviews, often quite satisfying to read, about works other than blockbusters. My own hobby horse, interactive fiction, has long been tied to a tradition of thoughtful reviews from its fans (perhaps unsurprising, since loving the medium enough to write about it requires a particular affinity for text). But when it comes to “triple A” titles — the big productions that get slices of retail shelf space, the games that gather so much news and attention and, unavoidably, enjoy a great deal of cultural cachet — I honestly don’t know where the worthwhile reviews for these lurk.

Tags: reviews.

Though I myself have yet to buy into tablet technology, I have had the pleasure playing Days of Wonder’s Small World on Zarf’s iPad a couple of times. I can objectively tell you that I like it a lot, based on the fact that he’s clobbered me at it both times and I still want to play it again. Since then, I’ve watched my Twitter circle get really excited about The Coding Monkeys’ excellent iPhone adaptation of Carcassone — due for an iPad update this summer — and I’ve also been turned onto Luigi Castiglione’s loving iPhone/iPad implementation of the Italian folk game Scopa, worth seeing just for the beautiful Neapolitan card deck it uses. I see more than mere coincidence in my discovering all these at once.

Though I myself have yet to buy into tablet technology, I have had the pleasure playing Days of Wonder’s Small World on Zarf’s iPad a couple of times. I can objectively tell you that I like it a lot, based on the fact that he’s clobbered me at it both times and I still want to play it again. Since then, I’ve watched my Twitter circle get really excited about The Coding Monkeys’ excellent iPhone adaptation of Carcassone — due for an iPad update this summer — and I’ve also been turned onto Luigi Castiglione’s loving iPhone/iPad implementation of the Italian folk game Scopa, worth seeing just for the beautiful Neapolitan card deck it uses. I see more than mere coincidence in my discovering all these at once.

The iPhone is no stranger to board and card game adaptations, but something new seems to be afoot, driven by the little phone’s newer, corpulent cousin. Even with relatively few datapoints, I feel confident that tablet computing (and do note my careful non-namebrand specificity here) is destined to significantly boost public exposure to good, modern board games. Tablet-based games aren’t simply a digital adaptation of tabletop games; they are tabletop games, though of an entirely new sort.

Tags: arcade games, digital games, games, ipad, jmac on games, nostalgia, tabletop games.

In terms of popular culture, May 2010 goes into the annals under the headline “The month that Lost ended.” For some of us, another fact about the month is at least as significant: Valve released its Steam content-delivery service — and corresponding a passel of new games — for Mac people. And for me in particular, this meant that I could immediately start playing Torchlight on my Mac.

In terms of popular culture, May 2010 goes into the annals under the headline “The month that Lost ended.” For some of us, another fact about the month is at least as significant: Valve released its Steam content-delivery service — and corresponding a passel of new games — for Mac people. And for me in particular, this meant that I could immediately start playing Torchlight on my Mac.

While one of these things is a game and the other a television show, both represent implementations of the thing I’ll call Blow’s Treadmill, that diabolical device eloquently deconstructed by Jon Blow in a talk we’ve linked to before. Blow’s Treadmill, in a nutshell, describes any system of game mechanics that give a game player a sense of accomplishment and advancement when, for all practical in-game purposes, they remain right where they started.

While the Treadmill criticism is most frequently levied against CRPGs (Blow’s archetypical example is World of Warcraft), Matthew “DefectiveYeti” Baldwin applied it admiringly to Lost in an excellent essay from a couple of years ago:

During each show you gain a little experience in the form of new information: about the island, the characters, or both; every four episodes or so you level up, as some (allegedly) major piece of the overall puzzle falls into place. After leveling up in a CRPG, you typically head to Ye Olde Flail ‘N’ Scented Candle Emporium, sell all your current equipment, and buy the improved weapons that your enhanced abilities now allow you to wield; likewise, after a revelatory LOST episode, fans chuck all their old theories into the dustbin and cook up new ones consistent with the revised facts. Then, having done so, each-the player of a CRPG, or the viewer of LOST-is handed a brand new quest, or puzzle, or plot plot. The ephemeral thrill of leveling vanishes, replaced by a longing to hit the next milestone. You never disembark from the treadmill, it just goes faster.

Tags: angband, digital games, games, jmac on games, roguelikes, television, torchlight.

I wish to make an extended footnote on last Monday's post, regarding further similarities I see between the comics and video game markets. When I was in high school I went through a profound comics-geek phase where, beyond the typical obsessive book-hoarding, I undertook to learn everything there was to learn about that medium's history (a full decade before Wikipedia came 'round, my son). I've long since sold my longboxes full of Mylar-bagged pulp, but that knowledge remains, and I can't help but get very tangential when I have reason to compare comics to any other medium. Having thus further established my nerdboy bloviation credentials:

I wish to make an extended footnote on last Monday's post, regarding further similarities I see between the comics and video game markets. When I was in high school I went through a profound comics-geek phase where, beyond the typical obsessive book-hoarding, I undertook to learn everything there was to learn about that medium's history (a full decade before Wikipedia came 'round, my son). I've long since sold my longboxes full of Mylar-bagged pulp, but that knowledge remains, and I can't help but get very tangential when I have reason to compare comics to any other medium. Having thus further established my nerdboy bloviation credentials:

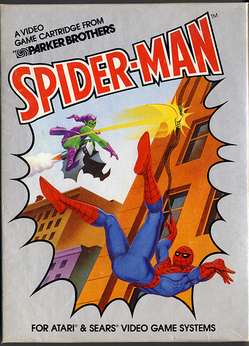

I see Valve Software today holding the same position in the overall media landscape that Marvel Comics occupied in the early-mid 1960s. In both cases, we have two experienced studios, neither the mainstream-recognized giants of their fields, who made an unusual decision: they chose to spend the creative capital gained from prior commercial success to quietly revolutionize their respective medium's dominant genres, rather than take the safer path of grinding out more derivative sameness.

Tags: comics, digital games, fpses, games, history, jmac on games, spider-man.

Two years after purchasing it (mostly because Portal was on the same disc), I have started regularly playing Team Fortress 2. My delay came from my general lack of enthusiasm about first-person shooters. My writing about it here comes from surprising insights about my own relationship with games that struck me soon after I began to play it.

Two years after purchasing it (mostly because Portal was on the same disc), I have started regularly playing Team Fortress 2. My delay came from my general lack of enthusiasm about first-person shooters. My writing about it here comes from surprising insights about my own relationship with games that struck me soon after I began to play it.

On the surface, TF2 is an intentionally silly online-only shooter where players, after choosing one of nine character classes, leap into a battle whose goal is one of the time-tested multiplayer FPS standards: capture the flag, king of the hill, or base attack/defense. Sometimes I mix it up with whichever random folks happen to be online when I'm feeling scrappy. My "real" games, though, occur on Sunday evenings with a group known as Clan Elysium who operate out of the web forum Geezer Gamers, a haven for grown-up Xbox Live fans. These times have proven to be some of the most fun I've ever had sitting on the couch with a controller in my hands, and friend, I'd logged a lot of hours under those conditions before this.

There have been three major effects of this experience. First of all, it's reignited my interest in online digital games, both as a player and a ludeaste, and led me to reconsider what kinds of video games deserve the treasure of my attention right now. It also threw some wood under Planbeast, the project I soft-launched last year and then all but ignored; a subsequent post I made to the Geezers' forum unexpectedly led to a small boom of use for that site, and I spent a happy week responding to bug reports that resulted in several significant improvements to the service.

But what I want to write about here comes from the surprising insight this game afforded me regarding the play style I favor, and what this teaches me about unexpected connections between very different kinds of games.