Monthly Archives: August 2010

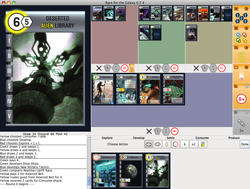

Turns out that both of the card games I wrote about Monday have officially sanctioned online versions. Dominion’s had an internet-playable implementation on the beloved BrettspielWelt for some time, but I only today got around to trying Race for the Galaxy’s computerized counterpart (pictured here). Both games are perfectly functional and free to play, but have a cost in… well, let us say that a polished user interface is not the top priority of either effort.

Turns out that both of the card games I wrote about Monday have officially sanctioned online versions. Dominion’s had an internet-playable implementation on the beloved BrettspielWelt for some time, but I only today got around to trying Race for the Galaxy’s computerized counterpart (pictured here). Both games are perfectly functional and free to play, but have a cost in… well, let us say that a polished user interface is not the top priority of either effort.

The brazenly unstyled HTML of Keldon Jones’ Race for the Galaxy page lets you know from the start that he isn’t out to impress you with a razor-sharp UI. But if it’s Race practice you’re after, I find his solution far more satisfying than the solitaire variant that comes packaged with the card game’s first expansion set. Keldon has been developing this AI in the sunshine for nearly a year, updating it frequently, and it’s very good. It consistently kicks my butt, anyway, whether with the base deck or any of the expansions — every one of which the programmer has implemented, and which you can mix in or out before each game.

In the tradition of one-hacker game-adaptation projects, obsessive focus on the rules and AI leaves the UI a secondary concern. Even with the simplest setup, it’s hard to tell with this Race board when anyone draws cards, for example, or which turn-phase is active. However, it quickly earned my trust that it wasn’t skipping any of the growing pile of interacting rules-exceptions that build up over the course over a single game. The requirement for every player to perform their own bookkeeping represents the weakest part of the physical game’s UI — one that I mess up all the time, to the annoyance of my friends, who grudgingly allow me to draw the bonus card I forgot to draw two phases ago. But this computer game quietly makes a non-issue of it, and I like that.

Tags: adaptations, bsw, card games, digital games, dominion, games, internet games, race for the galaxy.

If you’ll permit me a bit of silly personal nostalgia:

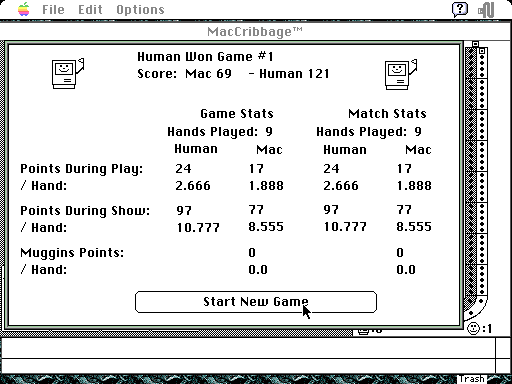

I came across this screencap, dating from the summer of 1994, while pawing through some old files. Apparently I managed to skunk my Mac at Cribbage — that is, I crossed the 121-point finish line before it hit 91 points, which my dad taught me counts as a double-win, especially if you’re playing for stakes — and was so thrilled with my achievement (and perhaps chagrined that the final scoreboard didn’t acknowledge the mustelid nature of my victory) that I took a screenshot and filed it away.

Please note that the size of this image was the size of my entire monitor at the time, at least in terms of resolution — when projected upon my screen via jet-age electron-gun technology, it measured 12 inches along the diagonal.

Incredibly, MacCribbage’s homepage still exists. Despite the page’s year-one webdesign (and, indeed, an on-page timestamp reading 3/14/95), you can still download the game there, though it’s been many years since any Macintosh computer has shipped with the means to run it.

Meanwhile, the game’s author, Mike Houser, has carried his work into the future with an iPhone version. My heart aches to see the stylistic differences in those two pages’ screenshots, comparing the pixel-perfect artwork of his 1990s work with the flat, anti-aliased color fills of the 21st century adaptation. Fortunately, he still sells a handful of Mac OS X-friendly solitaire games that make use of his charming original deck art, including those smileymac-visaged court cards.

The only thing worse than a flawed expansion to a good tabletop game is listening to some know-it-all groan about it. Complaints about expansions, after all, suggest their own unbeatable counterargument: So, don’t play with the expansions, then! It’s not like eschewing an expansion makes the basic vanilla game suddenly stop working, right? Perhaps we don’t enjoy Knightmare Chess, but we don’t therefore conclude that the original game is forever spoiled.

The only thing worse than a flawed expansion to a good tabletop game is listening to some know-it-all groan about it. Complaints about expansions, after all, suggest their own unbeatable counterargument: So, don’t play with the expansions, then! It’s not like eschewing an expansion makes the basic vanilla game suddenly stop working, right? Perhaps we don’t enjoy Knightmare Chess, but we don’t therefore conclude that the original game is forever spoiled.

So, in an attempt to turn such grumbling into an essay worth reading, let me turn it around: I hereby declare that it is not just desirable but possible to design an expansion set for a good game in such a way that actually improves the game as a whole, rather than simply making it larger. So this fact makes it that much more disappointing when a solid game releases an expansion that adds stuff, but fails to add an equal-or-greater amount of fun. Fair enough?

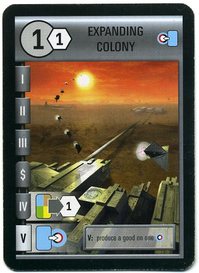

As it happens, I can find one example of each between two often-compared games of recent vintage. Dominion (Donald X. Vaccarino) and Race for the Galaxy (Tom Lehmann) are both quick-playing card games that have earned tremendous cachet from tabletop gamers in the last two or three years. (The Gameshelf has itself ruminated about both games, via Kevin and Zarf, respectively.) Both proved successful enough to spawn several expansions apiece; Race got its third such set into print earlier this year, and Dominion — despite being a slightly younger game — will see its fourth in stores by the holidays.

Let’s look at Race for the Galaxy’s general expansion philosophy. What comes in each of its little boxes?

OK, two of them are about dice.

Your Uncle Dudley’s Knucklebones appears to be the online gallery of a dice collector (with a casually Google-resistant identity). The mysterious blog contains only two posts, but the enormous latter entry contains many dozens of individual photographs.

The dice lay against a ruler on a white background, looking more like bullets in an autopsy, removed from their police report. The site offers no textual explanation of where any of the dice came from, or what purpose the more oddly specialized ones may have served. But if you’re like me, you’ll find delight in imagining the designs these little rolling-bones once played a part of. (Granted, the aim of the rather NSFW dice towards the end seem plain enough…)

I was interested to see that the first post, dedicated to the display of a single prototype 60-sided die design, mentions the fabbers at Shapeways.com. We’ve mentioned their contributions to the games-and-puzzles world before.

I have not read The Bones, but I probably should. It’s a collection of essays on dice edited by Will Hindmarch, and my fellow tabletop-game aficionados will recognize many of the collected author’s names — Costikyan, Kovalic, Selinker, the increasingly inevitable Wheaton, and many others. A print book is currently for sale, with an ebook edition in the works.

(Bonus aside: for a delightful coffee-table book about these most venerable gaming tools, Ricky Jay’s Dice: Deception, Fate & Rotten Luck, which pairs smart text on the history and culture of dice with truly beautiful and haunting photographs of our cubical friends by Rosamond Purcell. It’s still in print, and findable through the book-oracle of your choice.)

Finally, allow me to share with you the good news that God’s Number is 20.

With about 35 CPU-years of idle computer time donated by Google, a team of researchers has essentially solved every position of the Rubik’s Cube, and shown that no position requires more than twenty moves.

[ … ]

One may suppose God would use a much more efficient algorithm, one that always uses the shortest sequence of moves; this is known as God’s Algorithm. The number of moves this algorithm would take in the worst case is called God’s Number. At long last, God’s Number has been shown to be 20.

It took fifteen years after the introduction of the Cube to find the first position that provably requires twenty moves to solve; it is appropriate that fifteen years after that, we prove that twenty moves suffice for all positions.

I don’t pretend to fully understand exactly how this solution came about, despite the cogent explanations on that page, and its many interesting links to other Cube-fiends’ attempts at finding this elusive number, going all the way back to typewritten correspondence from 1981. But I am delighted to learn about such a vertiginous level of recreational puzzle solving — not solving the Cube, but solving a puzzle that’s made out of solutions to the Cube, a true meta-puzzle. All the better, I suppose, that I learn about it specifically because some folks have finally laid it safely to rest after nearly 30 years of shared effort. Less fundamentally frightening, that way.

Quite by accident, my last post reflecting on the trend away from difficult slogs in all kinds of games fell on the same day that several indie game developers banded together to blog in support of intentionally short videogames. My post and theirs drew inspiration from the same well, though; many of these posts pointed to the brilliant Limbo, which I wrote about on Monday, and the sniping it received from the enthusiast press for having a total play-length of less than ten hours.

As expected, Jon Blow writes a compelling (and short!) entry, after which he (like all the other writers in this exercise) compiles a list of links to the other participating game developers’ short-game essays (a list which, to my delight, includes Boston-based developers and Gameshelf friends Eitan Glinert and Scott MacMillan). Jamie Fristrom also caught my attention with a look back, with some regret, on decisions he took part in producing Schizoid and Spider Man 2, both long and difficult games which very few of their fans have played to completion. (In fact, I count myself among this impressed but unfulfilled majority in both games’ cases.)

My spur to finally write this acknowledgement came via Sean Murray’s “The Long Game”, in which he stands with the short-game fans, but then flips the argument onto its head in a defense of longer games (such as the one that his own studio develops). While I do appreciate the perspective, I can’t quite cross the bridge he builds there.

Arcade-style skill contests like Geometry Wars to one side, I’m very skeptical of any single-player videogame’s ability to “amaze and delight over weeks of play”, at least not with the unremitting intensity of novelty that defines the games on the Braid/Portal axis. Members of this family are short because they end when they’re empty, when they have no new things to show the player within their intentionally narrow play-domains. The tightest examples of the form establish their rules and spaces quickly, and then proceed to explore every interesting permutation of it, avoiding repetition in either game presentation or player activity. When the whole space is explored, the curtain closes (perhaps after a finale that ties up the frame story, if necessary).

At no point does the game suggest that it might be worth the player’s time to go tromp through a fifth procedurally generated dungeon, or scan an eighteenth planet for random-number “rare ores”, or what have you. They are not about escape, of spending as much time as you can away from reality before the game comes to a close (or becomes too boring to bear any further). Escape will always have a role in the world of videogames, but there is no good reason why new games should be judged in light of how expansive an escape they provide. Some games would rather try to enhance your life with brief and brilliant new patterns that will leave a mark on your mind than deliver a slow-drip soporific.

(Yes, there are always exceptions. Most multi-player games I hold almost entirely exempt from this line of reckoning, since I find them such fundamentally different experiences. Then again, I suppose I might want to label treadmill-based MMOs as exempt from my exemption. And where do half-breed board-gamey timesinks like Sid Meier’s Civilization fit into this? Well, perhaps that’s a column for another time.)

I haven't posted one of these since the Gameshelf got its stylish new (that is, Greek antiquarian) logo. But the fanboy I remain, so here's what Cyan has been whispering:

The Manhole for iPhone/iPad/etc is out. (App Store link) It's a whimsical children's story-or-environment -- worth exploring if you only know the Myst series.

Riven for iPhone/iPad/etc is marked as "coming soon". Riven is my favorite of the series, but I haven't played it since its original release -- it's notably hard to get running on modern machines. (Even harder than Myst, which has been updated and re-implemented all over the place.) I am seriously looking forward to this one.

Cyan also pushed a stack of games up on Steam. But if you use Steam, you probably saw that.

And finally, this teaser page was linked from Cyan's home page today (although I don't see it there now). The banner tag was "Never Let Your Timbers Be Shivered." What is it? Looks like some kind of resource-based explore-and-fight. With pirates. That's all we know -- except that a Cyan folk also dropped into a forum thread and linked to this MP3 file.

I find it interesting, as an aside to yesterday’s column, to examine how applied cruelty has fallen from favor across multiple game media over time.

I chose the word “cruelty” quite intentionally, referencing Andrew Plotkin’s famous Cruelty Scale for interactive fiction and adventure games in general, even though that particular yardstick actually hasn’t seen much use lately. Today, adventure games worth playing rarely require players to keep more than one save file. Gone, largely, are the days where players must save early and often, managing an entire tableful of carefully named save-positions for easy — and inevitably frequent — access.

(In fact, the main reason the concept came to mind at all was Sarah Morayati’s excellent but unforgiving Broken Legs, a game that overtly classifies itself as belonging to the thorniest rung of Zarf’s scale, the one where games merrily — and silently — allow you put them into an unwinnable state. The game is an intentional stylistic throwback to certain knotted puzzlefests of yore, leaning against the modern trend that favors narrative over puzzles.[1] The game (which took second place in last year’s IFComp) succeeds because the player character — the irascible, scheming drama princess Lottie Plum — is an acerbic joy to play, and she tells a rollicking story, even if she herself is more interested in sabotaging all her peers than actually performing on-stage. But it’s a story you’ll need to patiently play though several times, if you want to give Lottie the best ending.)

Board games, too, have largely become a stranger to cruelty. When we filmed Diplomacy last year, I initially felt disappointed that no players got eliminated from our game — an ever-present possibility in this game from the 1950s. Not only would that have added easy drama to our unscripted, televised narrative, but we could have capitalized on the very concept of a board game that can “kill” players, forcing them to stop playing while their friends keep going — something that seems flatly outrageous by today’s tabletop design standards. Never mind certain shambling zombie-games that still manage to keep up this pretense…

And when’s the last time any of you with a tabletop RPG bent have ever had a character die — or, at at any rate, die without your full consent as a player? A few years ago, some local friends decided to play a game of first edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, taking the circa-1975 rules literally as written, with the GM making no exceptions. This was back when phrases like the character must make a saving throw versus poison or die could be found dozens of times in any given rulebook or adventure description.

The result, of course, was a massacre, with individual players sometimes ripping through several character sheets within a single session, as their powered-up superheroes succumbed in a heartbeat to unlucky die rolls around falling-rock traps or venomous spiders. Nobody tried terribly hard to develop their doomed characters’ abilities, nor was there much call for inventing a completely new persona for each of their mayfly alter-egos. Clearly, these rules fit much better to a time when the game still had one foot in the category of miniatures-based wargaming.

So, the next time you’re playing a game of any sort that recognizably punishes failure without diminishing your level of fun, thank all those before you who have gave their in-game lives — over and over and over again — for the sake of inspiring better game design.

[1] Sarah reminds me about Jon Ingold’s delectably evil Make it Good, another capital-C Cruel game of recent vintage that is far larger and more difficult than her own work. The key point for me, though, is that I played Broken Legs more recently, and my memory is weak. So there’s that!↩

Tags: board games, cruelty, dungeons and dragons, games, if, rpgs.

I really enjoyed Limbo (Arnt Jensen et al), holder of this year’s Portal-Braid Memorial Award[1]. Beyond being a densely packed and very clever puzzle-platformer of exactly the right length, it has some interesting things to say about the concept of “death” in videogames, and how this concept has evolved over the last quarter-century.

I really enjoyed Limbo (Arnt Jensen et al), holder of this year’s Portal-Braid Memorial Award[1]. Beyond being a densely packed and very clever puzzle-platformer of exactly the right length, it has some interesting things to say about the concept of “death” in videogames, and how this concept has evolved over the last quarter-century.

From its title (and unnervingly flyblown title screen) through its murky shadow-puppet audiovisual aesthetic, Limbo makes death a thematic focus long before it actually shows up as a gameplay element. And death, in the traditional videogame sense, will visit its player many, many times: your on-screen character succumbs to an obstacle, you get a little “oopsie” animation, and you must try again to overcome it.

However, over the course of a single Limbo playthrough you will die far less often than you’ll send Mario, the unironically happy little bouncyman, gurgling down into his game-over grave while learning to play his own candy-colored signature game — even though we don’t see Super Mario Bros. as a particularly macabre title. What’s going on here, exactly, beyond the obvious differences in visual design?

Tags: death, digital games, games, limbo, xbox games.

Our August meetup will be on Monday, August 30, at 6:30 in 14N-233 at the MIT campus. See our website for more details about the group. This month’s agenda:

- We’ll be the first to check out a new adventure game from GAMBIT.

- We may check out a few bits of GET LAMP.

- If it’s out in time, we’ll likely flip through some of the new book on writing IF, Creating Interactive Fiction with Inform 7.

- We’ll play the IntroComp 2010 games that we didn’t get to last month, and we’ll discuss the results of the competition (which came out this past weekend).

- If our Tufts contingent is represented, we’ll talk about how planning for IF month at Tufts (October) is coming along.

All are welcome, and please feel free to come with your own suggestions for things to do/discuss.

Tags: boston, if, interactive fiction, meetup, pr-if.

First, I'd like to say thanks to Jason McIntosh, Kevin Jackson-Mead, and Andrew Plotkin for the opportunity to write this series; it's been extremely useful to have a forum for clarifying my own ideas on magic systems. I'd also like to thank everyone who read and commented on each blog entry. Your feedback has been very helpful, often bringing new games to my attention as well as offering helpful insights into existing games and concepts. When Jason and Kevin first mentioned the idea of guest-blogging on the Gameshelf, we agreed that a limited duration of a couple months made the most sense, in part so that other guest bloggers can carry forward the mission of the Gameshelf in many exciting ways.

And, while in one sense I'm wrapping up this particular series, I feel more like radiating outward in many directions, because the opportunity to write here has inspired so many ideas for further exploration. Magic is an explosive nexus that doesn't react well to being contained or bottled up. It's best to answer the question: where next? And the inevitable answer is: many directions. This installment is written under the aspect of the sign of chaos (as invented by fantasy writer Michael Moorcock and adopted equally in games like Warhammer 40k and Peter Carroll's occultist movement Chaos Magick). In its positive sense, chaos is a signpost pointing toward a multitude of possible paths, liberating creative energy rather than confining it.

As far as my own creative work goes, I'll be posting a new video of my Arcana Manor interface on Youtube soon, since I now have working code in the form of drag and drop elements of spell grammar feed into array, as well as a function for matching the changing contents of this array with a database of spells. Using GlovePie, I now have keyboard input controlled by voice, as well as drawing input via the Grafitti bitmap drawing library in Actionscript 3.0. I'm currently working with mouse gesture recognition libraries in order to allow drawing gestures to be fed to the array, thereby making drawing a fully integrated aspect of the interface.

Tags: games, magic, magic systems, magick, transmedia, video games.

Since this blog series is called "Magick Systems in Theory and Practice," I feel that I should talk about my own practice in terms of concrete design of magic systems. For the past year and a half or so, I've been working on a project tentatively (and perhaps temporarily) titled Arcana Manor.

For the sake of consistency, I'll reproduce some of the most recent design document, starting with the game's elevator pitch.

"In Arcana Manor, the player wields a uniquely immersive and symbolic magic system to defeat the demons of a surreal Gothic mansion and unlock its secrets. Arcana Manor is a ceremonial magick simulator with an elaborate system of gestural sigils, incantations, colors, and sounds that makes players feel like true adepts, not mere button-pushers.

The magic system has these overall goals:

• to let players feel like they are the ones casting the spells rather than watching a character cast them

• to allow players to express and re-configure symbolic ideas differently in order to warp and alter reality, i.e. the system changes and adapts to different players' behaviors and personalities

• to be learnable, in part, through experimentation and trial-and-error so that there will be mystery surrounding the system; while the system is rigorously rule-based, a part of magic should remain magical in the sense of unpredictable, hidden, and knowable only through direct experience.

The conceptual framework of the magic system is based on ideas derived from authentic mystical and occult lore, in which magic is a metaphor for the power of the creative imagination.

• Players cast spells through their mastery of arcane knowledge and the symbolic correspondences of ritual

Aleister Crowley, Liber 777: 'There is a certain natural connexion between certain letters, words, numbers, gestures, shapes, perfumes and so on, so that any idea or (as we might call it) "spirit", may be composed or called forth by the use of those things which are harmonious with it, and express particular parts of its nature.'"

Tags: actionscript, arcana manor, flash games, games, magic, magic systems, magick, torque, unreal engine, video games.

A personal note: After lugging them around for many years, I finally found a better home for my Atari VCS, its many controllers, and the sixty-odd game cartridges I had collected for it while I played it throughout the mid-to-late 1980s. Last Friday, I donated the whole lot to the GAMBIT Game Lab in Cambridge. At right is the one last family portrait I snapped on my phone before packing them all away one last time and heading to the subway.

A personal note: After lugging them around for many years, I finally found a better home for my Atari VCS, its many controllers, and the sixty-odd game cartridges I had collected for it while I played it throughout the mid-to-late 1980s. Last Friday, I donated the whole lot to the GAMBIT Game Lab in Cambridge. At right is the one last family portrait I snapped on my phone before packing them all away one last time and heading to the subway.

I’d been considering doing something like this for long time, but what finally tipped me over the edge was seeing Toy Story 3. I found myself unable to avoid humanizing my poor Atari system, stashed away in the dark for so long, holding out hope after all these years that someone, anyone would set it up once again play with it.

For years, I could dismiss such thoughts by telling myself that I’d get around to it myself, someday. But it occurred to me only this year that I’ve irrevocably lost this ability. The Atari VCS cannot, by definition, work with flat-screen LCD televisions. Like other early home videogame systems, it displays video by, essentially, hacking the television it’s connected to. Lacking any modern notion of video memory, the VCS uses a variety of tricks that all assume the presence of an electron beam sweeping across the screen, painting pixels row by row. VCS games must carefully time their internal operations to the relentless march of that beam.

I bid farewell to my last such television in 2008, giving it to a friend the same day I bought my Xbox 360 and my first LCD HDTV. I didn’t think at the time about what else I gave up along with it.

I could have responded to this belated realization by trashpicking an old CRT TV, setting it up in the corner of my apartment somewhere, and finally building my own little Atari shrine. But, faced with it, I found myself thinking: why emulate Al’s Toy Barn when I could instead pass it along, where it could do some good?

I’m pleased with its new home, and have great faith that the faux-woodgrained little box and its dozens of boxlets have a bright future ahead of them as an object of study for today’s game students. Most of them wouldn’t even have been born yet when I received the system from my older brother’s friend in a big paper Stop ‘N Shop bag; he had loved it for years before that, but gave it away to a game-loving kid he knew when it was time to move away. Maybe I should have done something like that myself, perhaps when I myself went away to college. But I’m happy I finally did it now. (And I used a canvas Stop ‘N Shop bag, this time around.)

Confidential to Clara: I meant what I said about being willing to take on all comers at Indy 500. I still have my one-button driving-controller chops, even after 20 years. I just know it.

Tags: atari, gambit, game studies, mit, nostalgia.