I have decided to spend less time playing solitaire digital games. I won't hold myself to a zero-tolerance limit on this; petit fours indie efforts of all stripes certainly remain fair game, for one thing. (Most recently across my plate: Continuity. Delicious.) But high-budget blockbuster attention-sinks are off the menu for now. Here you observe me not playing Bioshock 2, even if I rather liked the first game. Now see how I sit perfectly at peace about leaving Grand Theft Auto IV unfinished, though I certainly had fun banging through its first third or so last Thanksgiving.

I have decided to spend less time playing solitaire digital games. I won't hold myself to a zero-tolerance limit on this; petit fours indie efforts of all stripes certainly remain fair game, for one thing. (Most recently across my plate: Continuity. Delicious.) But high-budget blockbuster attention-sinks are off the menu for now. Here you observe me not playing Bioshock 2, even if I rather liked the first game. Now see how I sit perfectly at peace about leaving Grand Theft Auto IV unfinished, though I certainly had fun banging through its first third or so last Thanksgiving.

The experience with Team Fortress 2 I described a couple of weeks ago has had a clarifying effect on my relationship with games. I've come to realize that, more than questions of art, story or mechanical design, it is games' ability to bring people together through play that I find their most interesting and engaging aspect. I mean this in all of games' non-solitaire forms, from board games straight through to Super Smash Bros. And, yes, even to sports, though you won't mind if I leave it to others to write about that...

Of particular interest to me today is online multiplayer games, a field of vast potential whose successes uplift me as much as its shortfalls and untapped areas intrigue me. I admit that I feel a little defensive about this, when the digital realm has lately enjoyed a lot of very interesting experimentation with local multiplayer games, those that you play with friends in the same room. (For example, have you seen Pax Brittanica yet?) Online play, meanwhile, seems much less vibrant at first glance, dominated by MMOs and shooters on one side, Farmville on the other, and not much in between.

But, given my own history as a game-player, my specific attraction to online play doesn't surprise me at all.

I first logged into a MUD -- one of the text-based forerunners of today's MMOs -- in the fall of 1991, a month after starting college. It happened in October rather than September because it took an entire month for me, working alone from a cold start, to acclimate myself to UMaine's mainframe system, discover and get the hang of Usenet newsgroups, and then stumble across online discussions about these games I'd heretofore only dreamt about.

(Well, yes, I'd also read an article about one in Dragon magazine, around 1988 or so. The author wrote of their experience slaying goblins in a cave with a friend, and then attending the wedding of two other characters. Utterly fantastic, yet they made it quite clear that all the players, the author included, were seated at mutually remote computer terminals, and that the gameplay was a mix of digitally-mediated dungeon-crawling with player-directed storytelling. I had a computer terminal too, a lovely beige-brown Atari 800 with two cartridge slots, but no notion of how to make it talk to other computers. I wanted so badly to be part of this experience, but all I could do for the next few years was dream.)

One evening in my dorm room, I finally puzzled out how to use the telnet command to connect to a multi-user text game running, probably furtively, on some other school or science lab's server. I do not recall now which MUD it was. What I do know is that this would be last day I would ever know true boredom. It's hard for me to relate how profound a change this was, doubly so without sounding like a sympathy troll. The fact is, though, as a shy and nerdy kid in the 1980s, I was alone in ways that, I suspect, very few people born into the western world after 1990 or so can ever understand. Before the web, it was hard for a lonely and introverted child to find a community of peers, and so I didn't. And as a result my childhood was largely defined by long stretches of nothing at all.

The reason that video games affected me so profoundly was that I really had so little going on that the awe and mystery offered by my too-infrequent visits to the arcade were an energizing glimpse into a higher world. Beyond making me like unto a little old Catholic widow who goes to Mass three times a week, it also instilled in me the notion that the path to enlightenment lay through games, and I would carry this candle to college.

And so it came to pass that the moment I created my first character on a MUD, I crossed through a personal singularity. I may not have consciously thought Oh, here's where they've been as I first encountered the textual avatars of the people who dwelled there, but sure enough I felt an instant sense of belonging with them. It was the start of what I consider to be my real life, with my current personality. It's the day I was born again.

So, yes. Online games are interesting to me.

I would play on MUDs every day for the next ten years. (Play, per se, would often find itself subsumed in favor of socializing with friends. But given MUDs' fantastic contexts, the element of play was always present, even when it wasn't always actively exercised.) I phased out of it only as I entered the next stage of my life, moving from Maine to Boston and living, for the first time, in a truly dense community of other game-players. Thus did I drink deep of the tabletop hobby, and while I certainly never lost my affinity for digital games - no more than I stopped watching movies, or reading novels - it would be nearly ten years again before I found my way back to the particular joys of online gaming, even if the shape of the game that drew me back was completely different.

And yet, with ten years apart from it, and ten years more experience as an amateur producer of game critique and all-around armchair ludologist, all of the shortcomings and unfulfilled potentials of the online-play world become all the more apparent to me. Though nobody's asking for it, I am called to sink my attention into this field, and that means taking my attention away from something else. So, for now, no more 60-hour slogs through the Fallout wasteland with nobody other than script-driven NPCs to sing my ballad. With a smile I plunge myself into the multiplayer miasma, and I hope to find some interesting stuff to write home about.

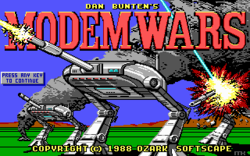

Image Credit: Splash screen from Dani Bunten's Modem Wars (1988), one of the first commercially published online multiplayer games.

So what's "Megaton"?

(This has been a service of "Dumb questions for all", a wholly-owned subsidiary of Zarfco.)

As you know, Bob, "Megaton" is the name of the first town you encounter in Fallout 3, a very popular single-player adventure game of recent vintage that I myself have sunk dozens of hours into. Therefore, I thought it an apt symbol for the entire sub-medium. And anyway it sounds cool.