Monthly Archives: July 2010

It's been a crazy couple of weeks in IF, and we're expecting several more months of crazy on the horizon.

Aaron Reed's book Creating Interactive Fiction with Inform 7 has gone to the printer. You can pre-order it through Amazon. This is an I7 tutorial which concentrates on -- well, as the title says, on creating interactive stories. It's not a programming reference manual, and it assumes no knowledge of programming. I haven't seen this yet but by all reports it is fantastic.

Jason Scott's movie GET LAMP has gone to the printer and come back. You can order on the web site. He says that they'll start shipping out next week.

The Gameshelf's own Jason McIntosh posted his own IF video... oh, wait. You already saw that.

We invited people to get together at MIT and play Zork (the original MIT mainframe version). A whole lot of people did! It was a bunch of fun and we will be continuing the IF-playing series.

A magic system is the sum total of its mechanics, interface, visual art, audio, narrative, and mythology, because a game is defined by its experience and experience consists in all of these components. Since a magic system simulates the alteration of reality by the will through the agency of metaphysical forces, all of the components of a magic system (such as visuals and audio) should ideally be pervaded by the metaphysics that the system is designed to simulate. Yet, a magic system that pushes its metaphysics to the peripheries of its art style and narrative is taking the easy way out, with the result that hardcore players will tend to ignore what they regard as mere flavor and fluff in favor of the mechanics through which they can gain concrete strategic advantage. A designer who aims to enrich her magic system through the introduction of metaphysical profundity will want to unify metaphysics and mechanics so that the understanding of esoteric concepts will improve a given player's ability to succeed in the game. Then, the hardcore gamers will tend to have the greatest, deepest grasp of the game's metaphysics because they stand to benefit most from such a comprehension.

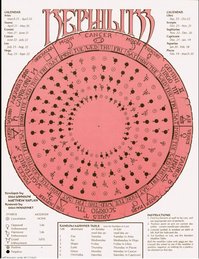

How, then, could mechanics and metaphysics be intertwined? The conjunction between the rules and affordance of a game with its philosophical implications can sometimes best be observed in non-digital games, in which the skeleton of mechanics tend to be unobscured by moving graphics and sound. One example of intertwined metaphysics and mechanics is *Nephilim*, the French game of "occult roleplaying" alluded to in last week's blog entry.

Among *Nephilim*'s many interesting mechanics is a modifier that changes the effect of a given spell according to the astrological signs associated with hours and days of the week as they interact with various elemental correspondences. The system is sufficiently complex that a Game Master's Veil (i.e. screen) includes a pentagram-shaped dial with windows that can be placed over a complex astrological table in order to calculate the modifier every time that a spell is cast. The astrological modifier and its expression through a concrete tool of turn-by-turn gameplay is one example of a metaphysical system of celestial influence and its conjunction with a game mechanic.

Tags: dragonlance, enochian chess, games, glass bead game, krynn, magic, magic systems, magick, nephilim, video games.

Since the dawn of Ravenhearst, the hidden-object genre has been with us. A screen full of junk, and a list of named items to pick out... Was it Ravenhearst, actually? The web is telling me that I should be blaming Mystery Case Files: Huntsville in 2005. That's still pretty recent, mind you.

2005 was also the year Myst 5 appeared, to not very widespread interest. Now, hidden object games didn't exactly displace the graphical adventure game. Those had been receding into their niche for years already. The Mystery Case Files were aimed at the newly-buzzlabelled casual-gaming market, meaning people who hadn't spent their teen years sweating over maps and joysticks. But the two genres have commonalities. Detailed environmental visuals led to a degree of convergent evolution: hidden-object games developed narratives, characters, dialogue -- even physical, mechanical, and symbolic puzzles. Sliding blocks and jumping pegs made their occasional appearance.

But the hidden object world stayed casual -- meaning aimed at a broad market; meaning easy. Picking a microscope or watermelon out of the onscreen welter might be time-consuming, but it didn't require puzzle-thinking per se. Hints were freely available to point out that last annoying dog collar. And when adventure-style or logical puzzles turned up, they stayed at the shallow end of the brain pool.

I don't mean to say I despise these games. Occasionally, when I want to kill an evening or two, I'll put down a few dollars and find me some objects. Recently, I've been trawling Apple's App Store -- because really, if you're going to spend an evening tapping on objects on a screen, the iPad is just the thing for it.

So I found myself looking at Mike Wilks's The Ultimate Alphabet, saying "Well of course." (App Store link.)

Tags: hidden object, ipad, mike wilks, ultimate alphabet.

Please enjoy Episode 8 of The Gameshelf’s video series. It’s about modern interactive fiction.

Interactive Fiction (a.k.a. text adventures), a curious cross-medium blending videogames and literature, defined computer entertainment at the start of the PC era. While it’s been decades its commercial heyday, the web has allowed passionate fans and creators to revive the medium through a resurgence of groundbreaking new work.

However, few gamers — even fans of more mainstream adventure games — know that this movement even exists.

In this ten-minute video, Jason McIntosh demonstrates some examples of modern interactive fiction, ponders the challenges that the medium faces in today’s digital-game landscape, and offers some starting points for players first discovering this unique kind of game.

Download it as a high-quality Quicktime file.

Additional credits, links and notes below:

For the Zork-playing event I mentioned earlier, there has been a slight change. It turns out that the room we were going to use didn’t have a projector, so we’ve acquired a new, better, easier-to-find room. It’s still at MIT, but it’s in Building 1 Room 135. Hope to see you there.

Tags: boston, if, interactive fiction, pr-if.

This week's blog entry is about magic systems and metaphysics--a topic which is to some extent a natural extension of last week's discussion of magic and horror, which introduced the representation of the supernatural as a defining trait of magic systems. This week's entry actually proceeds out of two coincidental occurrences: one is that I've been playing Magic: The Gathering [1993], Richard Garfield's famed collectible card game about dueling magicians, at lunch. This week I also happened to check out the web site for the game, where I was surprised to find text with a certain amount of metaphysical profundity and beauty.

The current expansion of Magic: The Gathering continues to develop the theme of Planeswalkers. In the mythos of Magic, each player is a Planeswalker, a dimension-hopping magician who duels with other mages by casting spells and summoning creatures. Planeswalkers are also a card type that functions somewhat similarly to an extra player or ally, with the ability to cast spells and summon creatures in addition to those cast or summoned by the player.

The website's description of a Planeswalker is quite striking and poetic, as in this excerpt:

a planeswalker's life is consumed with the exploration of the Multiverse, the discovery of strange secrets and experiences, and the plumbing of the depths of one's own mystic soul. The life of a planeswalker is a life of choice and self-determination, unrestricted by the boundaries of world or fate. With the freedom to travel and the power of magic, each planeswalker has the power to carve his or her name on the face of history

This description compellingly evokes the life of an adept and an initiate, guided by a triad of mastery, enlightenment, and imaginative travel. The devotion to an exploration of the multiverse echoes long-standing esoteric drive toward astral travel, fueled by an ethos of imaginative exploration that would render the Planeswalker a "mental traveler," in the words of William Blake. Moreover, this flavor text conjoins metaphysical ideas about astral travel with a metaphor for the lifestyle of a hardcore gamer, conceived of as existentially free and engaged with a number of different worlds rather than the single consensual reality of real life (or "RL"). Moreover, the trope of the Planeswalker takes its place within a larger cosmology involving the possession of an inner spiritual "spark" and its awakening through epiphanic enlightenment, often triggered by trauma. This imagery is based on certain strands of Gnostic belief, as described in Hans Jonas' classic Gnostic Religion and scattered throughout popular culture, including the novels of Philip K. Dick and the comic books of Alan Moore.

The strongest magic systems are those that can accommodate a simulation of metaphysics overlaps with and reinforces similar fictions. Continuing with my definitional iterations and revisions, a magic system can now be defined as a set of rules and symbols designed to simulate the alteration of reality by the exertion of the will operating through the agency of a metaphysical force. So what is metaphysics? By definition, that which is beyond the physical. This word is more accurate and inclusive than the similarly-charged term supernatural; metaphysical acknowledges nature-oriented magic (druidism, Wicca, the green side of the color pie) without being restricted to it (since playing with only green mana or druids would result in monotony and a lack of balance).

Is metaphysics just the story surrounding magic in a given game world, its lore? No. Metaphysics is the experience of magic, expressed through its mechanics, visual art, audio, interface, and control scheme. Those magic systems are strongest which can accommodate the richest, most mysterious, interactive experience of metaphysics.

Sorry for the short-ish notice. This is our second attempt at an IF playing group to complement our IF writing group.

The People’s Republic of Interactive Fiction Presents: ZORK

July 25th, 2 - 5 pm

MIT Campus: Bulding 1 Room 135. NEW ROOM!

Come and play Zork where it all started. We will be venturing together into the dungeons of the Great Underground Empire.

Inspired by Adventure / Colossal Cave, Zork was one of the first text adventure games, developed by a team of students at MIT back in 1977 on a PDP-10. If you’ve never played a text adventure game, this is your chance to experience the joys of playing through the command prompt by joining others in the adventure. If you’re an old Zork hand, help us track down in-jokes and historic references.

Also, we’ll be trying to broadcast the session on Ustream: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/people-s-republic-of-interactive-fiction-zork.

Tags: boston, if, interactive fiction, pr-if.

The relationship between magic systems and horror is hidden and unexplored territory, as secret as the black arts that lurk within the games themselves. Horror as used here refers not strictly to the genre of survival horror, which is a marketing construct invented in association with the first Resident Evil. Rather, horror-themed games include any game whose purpose is to evoke a sense of fear, dread, and the sublimity of unknown dark forces. Horror-themed games can be first person shooters, action-adventure games, and side-scrolling beat 'em ups. Magic is rarely the core mechanic of horror-themed games, often because players are put in the position of fighting magic through firearms and melee, or using magic only indirectly through artifacts. Magic and horror are intimately wedded in terms of themes but not in terms of direct player interaction.

Yet, horror games often have the most original and memorable simulations of magic in terms of atmosphere and mood. What horror games have to teach us is their atmospheric simulation of magic, the Gothic mood that they associate with magic through a combination of art style, audio, and (sometimes) haptics. If more closely melded with the core mechanics of games, magic systems in horror games can be superb examples of design and provide inspiration for other hybrid genres.

Yet, horror games often have the most original and memorable simulations of magic in terms of atmosphere and mood. What horror games have to teach us is their atmospheric simulation of magic, the Gothic mood that they associate with magic through a combination of art style, audio, and (sometimes) haptics. If more closely melded with the core mechanics of games, magic systems in horror games can be superb examples of design and provide inspiration for other hybrid genres.

Magic appears prominently in horror games because of an endemic thematic preoccupation with the supernatural, with emphasis on its dark side as the infernal and the demonic. With this supernatural element in mind, the definition of magic systems can be further refined and extended from last week's blog entry. A magic system is a set of rules and symbols for rigorously simulating the alteration of reality through the will by the agency of a supernatural force, whether conceived of as a genuine metaphysical presence, a symbolic construct, or an energizing psychological reality. In keeping with Crowley's axiom from Magick and Theory and Practice that "any intentional act is a magical act," any act of gameplay requires the operation of the will to achieve a desired result in altering a symbolic reality; therefore, any game mechanic can potentially be looked at as magic. This definition could theoretically be extended to include snowboarding and guitar playing if the experience of these activities approached the transcendent (which according to some Rock Band devotees, it certainly does). However, those genres that most embrace the representation and simulation of the supernatural will tend to exhibit interrelated mechanics that can most rigorously be defined as magic systems.

I can never resist the chance to follow up on two Gameshelf posts at once, so here you are:

The Silver Lining is a fan-made King’s Quest game that, as Kevin noted back in March, found itself cease-and-desisted earlier this year by the company that owns that IP. Rather than vanishing quietly, the project’s fans got the word out, bringing global attention not just to its legal plight but to the fact that the project existed at all. Certainly, the first I’d heard of Silver Lining was its “Sorry, we’re shutting down now” announcement page, concluding with a heartbreaking image of game-protagonist King Graham’s trademark cap lying abandoned in the dust. And somewhere nearby lay a link to a petition…

Today, I learn via a review by John Walker in Rock Paper Shotgun that the project has ridden the resulting wave of new fan support to overcome its legal disputes, and has also followed through and made its first episode available for play. It’s a short review, but then, it sounds like a very short game. It does make clear that the game attempts to pack a lot of narrative into tight quarters in novel ways:

Look at a vase in the halls of the castle and you won’t hear, “It’s a vase.” You’ll instead hear a tale about the Queen when she was young, playing in these hallways. Look at the floor and rather than being dismissed you’ll likely listen to lines and lines about how King Graham feels about the situation he’s in - his son and daughter-in-law’s wedding being interrupted by a mysterious, cloaked figure, who has put the pair into an undisturbable sleep.

(Rather reminds me of IF games like Bronze, actually, but that’s another rack of bells.)

I consider this news a twofer because Gameshelf reader JayDee offered up the site as a source of solid game reviews, one of several great responses I got to my previous post asking for exactly this.

I note with interest that the site seems to divide its reviews into two categories: “An Hour With”, providing initial impressions soon after a game is released, and (as is the case with this piece) “Wot I Think”, essays written after the reviewer has spent enough time with the game to fully digest it, perhaps weeks later. Many titles eventually get representation in both categories. I find this dichotomy an interesting tactic of dealing with the fact that games can often take a long time to absorb well enough to properly comment on, while acknowledging the reality of the pressures a review-based publication faces to react quickly to the appearance of new works.

Tags: fanfiction, if, interactive fiction, links, reviews.

This image is one of the ads that has been flitting across my Steam dashboard lately. It depicts two characters from Half Life 2, paired with the blurb “The best game ever made”, attributed to PC Gamer magazine. And it, alone, provides an excellent summary of why I don’t read game reviews very much.

This image is one of the ads that has been flitting across my Steam dashboard lately. It depicts two characters from Half Life 2, paired with the blurb “The best game ever made”, attributed to PC Gamer magazine. And it, alone, provides an excellent summary of why I don’t read game reviews very much.

This saddens me, becuase I would in fact love to regularly read a videogame reviewer or two, the way I follow a small group of film critics whose voice I’ve come to understand and trust over the years. My favorite film reviewers are sources of continual education and enrichment, not just about the work on the table, but about the medium and its history as a whole. But I find the field of videogame reviews so choked with the sorts of writers able to produce blurbs like the one in this advertisement that it’s very hard to find any other kind.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can confidently say that Half Life 2 does in fact represent groundbreaking work that anyone interested in the medium and its history should study — as discussed here before, it’s part of the canon. But neither HL2 nor its potential audience is well served by a ridiculous blurb like the one in that ad. If I heard someone say “This is the greatest book ever written”, I would assume that they were a religious person showing obligatory praise for their faith’s holy scripture. And even then, that person is not extolling the book’s literary merit, but rather its utility for spiritual improvement, or some other quality generally inaccessible to others.

That Valve can, six years later [1], continue to hold up this blurb with neither embarrassment nor (as far as I can tell) irony shows the much sadder fact: Both in 2004 and today, this kind of language is normal and expected from videogame reviewers. And that sentiment is, sadly, hard to prove wrong. And so you have tragic situations where a poor soul like me has no firm idea if, say, Alan Wake is worth the significant time-and-money investment to obtain and play through. I have no writer or publication that I can turn to with reasonable expectation of finding a review with an ounce of perspective.

To clarify: my dilemma more involves studio-produced, retail-sold works. More humble, independently produced games seem to be better served here. Sites like Jay Is Games and Play This Thing feature daily reviews, often quite satisfying to read, about works other than blockbusters. My own hobby horse, interactive fiction, has long been tied to a tradition of thoughtful reviews from its fans (perhaps unsurprising, since loving the medium enough to write about it requires a particular affinity for text). But when it comes to “triple A” titles — the big productions that get slices of retail shelf space, the games that gather so much news and attention and, unavoidably, enjoy a great deal of cultural cachet — I honestly don’t know where the worthwhile reviews for these lurk.

Tags: reviews.

It’s that time again. We’ll be having our monthly meetup at 6:30 on Monday, July 26, at the MIT campus in 14N-233. See our website for more details about the group. On the agenda so far we have:

- Talk about how Zarf’s Readercon talk went and what we might want to do regarding other local conventions.

- Take a look at some of the IntroComp games.

- Talk about what we might want to do for PAX East 2011 (it’s been confirmed for Boston for the next 3 years).

- Watch the latest Gameshelf episode! We’ll be watching the YouTube-sized Gameshelf #8: Modern Interactive Fiction.

And as always, everyone is welcome, even if you don’t know anything about interactive fiction and just want to sit and observe.

Tags: boston, if, interactive fiction, meetup, pr-if.

I went to a game night this past week at my FLGS (friendly local game store). One of the new games I played was Anomia. It’s a fun little quick-thinking social word game. It’s pretty similar to Jungle Speed but with words instead of grabbing. If that doesn’t tell you everything you need to know, read on.

In Anomia, there is a face-down draw pile of cards. Each card contains one of 8 or so symbols and a category (“Shampoo Brand”, “Restaurant”, “Radio Station”, etc.). On your turn, draw a card and place it face up on top of a pile in front of yourself. If at any time the symbols on two players’ top-most face-up cards match, those players race to name something from the category on their opponent’s card. Whoever manages to get something out first gets to take their opponent’s card as a point. Play continues until the decks run out.

There’s a nice tension between your turn and everyone else’s turn. When it’s someone else’s turn, you know what symbol is face up in front of you, so you’re just looking to see if that one symbol turns up. But on your turn, once you turn up the card, you have to see if your new symbol matches any of the other three. Switching back and forth between those modes, especially if everyone is playing quickly, is very mentally stimulating. And there are a couple of twists thrown in, in the form of wild cards (where it declares two different symbols as matching in addition to the normal matching rules) and lower cards being revealed when a card is taken for scoring (we had a chain of three scores in one of the games we played).

There was quite a bit of laughter in the game, and I think everyone had a good time. The game comes with two different decks, and after we played two games in a row with the same deck and found some of the same answers coming up, we made the rule that you couldn’t say something that had already been said, which made it even more interesting. And I can’t pass up the opportunity to mention that one of the points I scored with the category “Palindrome” was “Able was I ere I saw Elba” (generally, the shorter the response, the more likely you are to score a point, since we were awarding the point to the person who finished first, not started first).

And since I’m known as the person who hypes local things on this blog, I’ll mention that the game was self-published by someone living in Boston.

Tags: boston, card games.

The definition of a magic system introduced in installment one could be sharpened from "any set of rules designed to simulate supernatural powers and abilities" to "any set of rules and symbols designed to simulate the alteration of reality through the will." This definition echoes Crowley's first axiom from Magick in Theory and Practice ("magic is the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will"), though it can apply to games without requiring designers to buy into any particular philosophical scheme. Rather, an appreciation of magic requires only a little reflection on the profound mystery of the will: by deciding to do something, we can make it happen. For example, we focus our will to pick up a glass of water at lunch, and we do pick it up. Magic is an extension of similar taken-for-granted acts of will into a more profound longing: to control not just our immediate surroundings through the direct use of our body, but to shape nature, technology, other human beings, and the spirit world through the force of the will.

Perhaps most specifically, the fascination with magic stems from a desire to guide and shape the forces that govern the course of our individual human lives. The exercise of will to create change in life is murky and difficult, thwarted as it often is by forces both internal and external beyond our control. But in games, there is the potential of mastery, of understanding rules and then manipulating them through strategy in order to achieve a desired outcome. "Here I rule" is the marketing slogan of Magic: The Gathering, a declaration often accompanied by depictions of a skinny adolescent smirking confidently while surrounded by the fearsome monsters. As gamers, many of us identify with that sentiment.

Perhaps most specifically, the fascination with magic stems from a desire to guide and shape the forces that govern the course of our individual human lives. The exercise of will to create change in life is murky and difficult, thwarted as it often is by forces both internal and external beyond our control. But in games, there is the potential of mastery, of understanding rules and then manipulating them through strategy in order to achieve a desired outcome. "Here I rule" is the marketing slogan of Magic: The Gathering, a declaration often accompanied by depictions of a skinny adolescent smirking confidently while surrounded by the fearsome monsters. As gamers, many of us identify with that sentiment.

As magic systems in games evolve, various forms of alteration of reality become formalized into types or "schools" of magic to categorize the ways in which players can alter a simulated reality.

I have a new theory about IF. Okay, no. It's an analogy. It's not even much of an analogy, but let me change the subject. Pacing!

Let's talk. About pacing.

(Time passes.)

IF authors think about pacing all the time -- in a sense, everything an IF game is pacing. Why is there a puzzle at that point? Because you want the player to stop and engage with the story at that point. Why is some object in a closed (not even locked) chest? Because you want the player to slow down and take in the environment before proceeding. Why did you set up an implicit open action for that door? Because you don't want to slow down the player as he dashes through. Every decision about what to implement, what to split out, and what to bundle together, is a decision about how much attention you want the player to invest at that point.

This sort of pacing has its analog in the world of traditionally-written fiction. When writing a novel, you decide how many words to spend describing each plot event, each character and detail. That's familiar ground.

But then there's the broader sense of pacing: when is the character running for his life, and when is he catching up with his friends? When is she manipulating a hostile alien god, and when is she in the burn ward recovering from the consequences? In other words, how do you arrange different kinds of story action?

Tags: comedy, douglas adams, if, interactive fiction, pacing, theory.

As we enter midsummer, the interactive fiction landscape continues its long thaw out of a decades-long winter of deep obscurity. This is an exciting time to be a fan of the medium one could call indie games’ indie games, and I feel privileged to live in one of its geographic activity centers.

As we enter midsummer, the interactive fiction landscape continues its long thaw out of a decades-long winter of deep obscurity. This is an exciting time to be a fan of the medium one could call indie games’ indie games, and I feel privileged to live in one of its geographic activity centers.

To my eye, much of this motion comes from the continuing fallout from PAX East and the unexpectedly potent meeting of the minds that happened that weekend — not just among established IF authors and critics, but with lots of interested newcomers as well, many of whom help sustain the medium-transforming conversations begun in March.

The last few weeks alone have seen a rich mix of IF-related activity and discussion, which I shall now attempt to summarize:

The most recent SPAG leads with Harry Kaplan’s “How Suite it Was”, a lengthy retrospective of the goings-down at PAX East’s IF Hospitality Suite last March. Beyond Harry’s reporting, the piece collects and recounts various attendees’ memories of the event, and the impressions it left upon them.

The story also served to remind me of my own excitement about the possibilities of writing and publishing serialized interactive fiction, an idea I floated during the IF Outreach panel’s lengthy digression into the thorny topic of the medium’s commercial potential. Just a spitballed notion at the time, the idea grew on me quickly, and I filled several notebook pages with thrilled scribbles on the topic before PAX ended and therefore wiped the whole thing from my brain-cache. Rediscovering it months later, I find it just as thrilling of an unexplored area. Look for a column-length bloviation on the subject later.

Emily Short and Nick Montfort led an interesting exchange about IF interfaces on their respective blogs last month. Emily — one of the lead developers of Inform 7, which I will risk calling modern IF’s most popular language — wondered out loud if the bare-naked command-line prompt, while iconic to IF’s form, might have outlived its usefulness. Working from her notion of the command prompt as false promise (one of my own favorite takeaway notions from PAX), she explores many experimental player-input routes that other text-based games have investigated over the years, and proposes some new directions to try.

On his own blog, Nick — a champion of interactive text by profession — provides some pushback, defending pure-text input as being a natural pairing for pure-text output, and offering skepticism that any other system would ultimately prove easier for a new player to learn. The discussion bled out onto various other blogs and fora from there, and remains ongoing — see, for example, Horace Torys’ alternate interface mockups, and Sarah Morayati’s critique of IF’s library responses, the (in)famous I don’t see that here-type messages that are also, unfortunately, iconic to IF.

Tags: boston, if, interactive fiction, pax, pr-if.