I had to put down Deadly Premonition last week, after an all-day binge. Happily, the problem wasn’t the marathon session itself; far away from running a cynical, lizardbrain-exploiting reward-treadmill, my drive to keep playing had more in common with my occasional internet-enabled activity of gulping down a whole season of an excellent TV series all at once. There’s just too much to do before PAX weekend (which is to say, the 2011 IF summit), though. I’ll return to it later this month.

I had to put down Deadly Premonition last week, after an all-day binge. Happily, the problem wasn’t the marathon session itself; far away from running a cynical, lizardbrain-exploiting reward-treadmill, my drive to keep playing had more in common with my occasional internet-enabled activity of gulping down a whole season of an excellent TV series all at once. There’s just too much to do before PAX weekend (which is to say, the 2011 IF summit), though. I’ll return to it later this month.

What a strange, time-delayed sleeper hit this game feels like. Wikipedia tells me that the US saw its release a whole year ago, but I hadn’t heard about it before quite recently, when several friends started writing about it at the same time. First, Darius shared an intriguing vignette of gameplay experience — A full-budget console game about FBI agents who are also peeping toms? — and then Matt found himself unable to say much about it other than that it was his favorite videogame of 2010. After I mentioned on Twitter that I had picked up a new copy for less than $20 on Amazon, Courtney responded by writing an Agent York / Molly Bloom microslashfic, and I knew I was in for something unusual.

I’ll be frank: I love this game. Much as last year’s Amnesia used the sub-medium of the FPS to present a tense and interesting game where you can’t actually attack anything, Deadly Premonition may be the closest I’ve seen to applying the sandbox paradigm to tell a worthwhile story that isn’t yet another chronicle of a kill-happy psychopath (be it Grand Theft Auto or Oblivion).

Once through the somewhat shaky prologue and able to drive freely around the town of Greenvale, I found myself fully engaged with the story — rather, with the investigation, my internalized voice of protagonist Agent York corrects me. In drawing me in for hour after hour of exploration, Deadly Premonition offered the most wonderfully solid proof possible that you don’t need to make every game-verb a different act of violence in order to create a compelling story-driven experience in an open-world game environment.

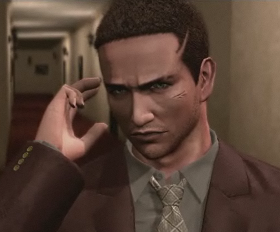

And maybe more than any title outside of pure-text IF I’ve played in recent memory, the major driving force is the player character. The eccentric Agent York, an overt homage to Agent Cooper from Twin Peaks, has a personality perfect for this role (and implemented superbly by voice actor Jeff Kramer). If he’s more than a little off-kilter in his approach, whether in solving murder cases or just in talking with other people, he’s just unbalanced enough to counterweight the often stilted writing which is perhaps inevitable from a cross-cultural product (in this case, a Lynchesque crime drama produced in Japan and then acted in American English).

Somehow, it all balances out into a world whose conversations are at least as fun to explore as its locations. I found myself repeatedly striving to find the next plot-advancing encounters or side missions specifically because I wanted to hear more dialogue involving York. How often does that happen in a console game? Given the choice between listening to an info-dump on Asari mating rituals while standing around in a space station or hearing an FBI agent hold forth on the commentary tracks found in Roger Corman DVDs while driving down a spooky forest road, I know where I’d rather be.

And just to seal the bargain, York’s most identifiable dialogue quirk is as irresistibly quotable as it is deliriously meta-gamey (no spoilers here). I quickly discovered, on Twitter and elsewhere, that suffixing one’s utterances with “Right, Zach?” has become a cake-is-a-lie-style watchword for smartypants videogame snobs (hello!) to identify one another.

And all this despite the fact that the game appears to be built on a survival horror engine, or at least has the air of a survival-horror project that had a mid-life career change. Interface elements and tropes specific to that sub-genre occurring throughout the whole experience, even when you’re miles away from any zombie-popping action.

Zombies do require popping from time to time, and I don’t yet know quite what to make of it. Their appearance seems to act as a pacing mechanic so that you don’t rush through the peaceful portions of the game too quickly, such as with the shadow creatures in Ico. But unlike that masterpiece, the combat scenarios in Deadly Premonition seem entirely modal — the game lurches into a level of Resident Evil 4, more or less, and you must clear it before continuing the investigation. With a handful of exceptions, these are the only times in the whole game York uses his weapons. As Matt notes in his review, this is among the weakest parts of the experience, even though it’s apparently where the game allows its survival-horror roots to assert themselves.

The game does at least drop some hints that there’s some meta-narrative winking afoot with the shooty parts as well; we’ll see. Maybe it’ll all become clear by the end. I very much look forward to completing this title and writing more about it from that perspective.